Editor's note: If you struggle at times to get your kids out for a walk in the woods or other nature outing, yet feel in your bones how important it is for them, you'll appreciate this gem of an essay by author Julie Zickefoose, which we discovered on ParentMap contributor Jennifer Johnson's blog. For more on why time outside is critical for kids, see also Kathleen Miller's July 2012 article.

It’s fairly typical of me, and other birdwatchers on a foreign trip, to be focused on seeing new birds. That first morning at the hotel, even if it’s in a city, can be electrifying, as we hear songs and calls unknown to us, and burn to learn out of which exotic bill they issue. So I was fidgeting a bit as I learned that my group, traveling Guyana’s interior, was scheduled to visit two rural schools. The children had programs they’d prepared for us. It all sounded very nice and birdless. But the children had been waiting all day yesterday, dressed in indigenous costumes, and we didn’t show up — rain had changed our schedule. Today, we had to show up.

We lined up on outdoor bleachers, I feeling tall, pale and awkward, as the kids filed out, dressed now in their everyday uniforms – sunny yellow jumpers and white shirts. From the moment the children opened their mouths to sing, they had me. If our elementary school choir teacher had been able to coax such angelic melodies out of my kids and their classmates, she’d probably faint on the spot. There was no pretending to sing, no too-cool-for-school inattention. These kids sang, really sang, and they melted my heart. They danced, telling of their traditional agriculture and hunting with their motions.

I was transfixed by the timeless beauty of their faces. They sang a song they’d written about their village, the beauty of the sun coming up over the mountains; brown-skinned Amerindians in every house, and tears started rolling down my cheeks.

I thought about my kids standing in just such rows, singing Jingle Bells or Sleigh Ride, and wondered what might happen if they were asked not to sing a song they already knew, but to write and perform an original song of gratitude to the place they live, the mountains and sky and community they enjoy. It’s not that they couldn’t do it, and do it well. Thing is, they’ve never been asked.

From there, I thought about what we ask of our children, and I’ve been thinking about it ever since. It is currently in vogue to note that children “these days” don’t evince any interest in the outdoors; that their favorite place to play is “where the outlets are.” And it’s true, in large part.

When I was nine, my son’s age now, I got home from school and headed for the small patch of woods behind our house in suburban Richmond, Virginia. There, at the age of eight, I saw the blue-winged warbler that was to be my spark bird; there I listened to catbirds and followed wood thrushes as they hopped springily in the dappled leaf litter. In that five-acre patch, ringed all around by houses, I flushed an October woodcock, rushing back to the house to my books to find out what the odd-looking bird with the whistling wings might be.

I watched a family of great-crested flycatchers, something I’ve never had the chance to do since. I found their nest by noticing a long trailer of house insulation coming out of a hole in a dead snag, and wondering why it was there. I watched the nest and saw their babies fledge, voicing miniature wheep! calls as they lined up, tailless, on a branch to be fed. I poked into our bird houses for flying squirrels and nuthatch nests, followed pileated woodpeckers as they foraged. I was Harriet the Spy, finding out all I could about birds. I chased down any song or call I didn’t recognize, and I learned that brown thrashers will eat doughnuts and cooked spaghetti. There, I became a naturalist.

I know that, if we aren’t bemoaning how lonely and lousy they were, we all tend to idealize our childhoods. And I know that I sound like Grandma, who claimed to walk miles through knee-deep snow to school. But the truth is that my children lead a very different after-school life than did I, when afternoon television was Mike Douglas or Dinah Shore, when there were no computers or Wii’s singing the siren song of oblivious absorption, when the outdoors simply seemed so much more wonderful than the living room.

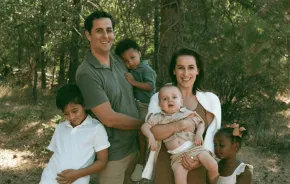

I enjoy taking my two children on hikes, hikes that start out from our kitchen, as we fill a backpack with water bottles and snacks, then wind out through the meadows and into the woods, our Boston terrier levitating in joyful circles around us. They won’t go into the woods on their own, as I did. I have to take them, have to line up incentives, often chocolate ones, to encourage them. Whatever it takes. When Liam was still small enough to pick up and would resist, I would lift him off the couch, throw him over my shoulder like a sack of sugar, and carry him outside. I’d lug him over my shoulder until we were too far from the house for him to run back, then set him down and tell him to lead the way. He could choose where we went — down to Beechy Crash or around The Loop, to the beaver pond or the overlook. That appealed to his competitive side, and he’d take off at a brisk pace, choosing the way. Whatever it took.

Now that they’re older — nine and 12 — and take great pride in outpacing me (when did that happen?), hikes are something we all look forward to. I still have to initiate them, sometimes have to wheedle, but they’re troopers now, and they know that complaining will do them no good. We pick a destination and go. And as often as not we take their friends along. It’s fascinating to watch kids from other home environments adapt to this unaccustomed and fairly rigorous regime.

On a recent hike with a pair of six-year-old twins and their brother, 7, one of the twins — Noah — lay down several times, saying he was too tired to go on. This was a problem, as he was too big to carry, even if we’d wanted to carry him. We joked that we were taking Noah for a drag. Some tough love was employed. We finally reached our destination—a series of beaver dams, each more spectacular than the last. His brothers were impressed, enthusiastic. Noah screwed his eyes shut, refusing to look. And then we told him that we were exactly halfway home, and every step he took would bring him closer to home. And Noah stepped out front, like a horse who smelled the barn, and never let us overtake him from that moment on. It wasn’t that he couldn’t hike three, almost four miles. It was that he’d never been asked to.

It isn’t that our children can’t appreciate the outdoors. It’s that we haven’t asked them to. Our daughter, Phoebe, came home from school one day with an assignment: to describe her favorite place. And she wrote an essay about a night in New Mexico, when we’d dragged the kids out of bed with the stars still high in the sky, to go freeze on an observation platform, waiting for sandhill cranes to lift off from their night roost. On the way to the refuge, an enormous meteor streaked down, seemingly right into the field alongside our car. There was no missing it; it lit up the whole sky with its blazing trail. Phoebe wrote an essay about that inky-black morning, the meteor; about New Mexico’s vistas and mountains and incomparable colors, about how she’d like to live there someday. My heart overflowed, because I’d felt bad about dragging them out of bed in the wee hours, about making them stand with us in the ice-cold wind, waiting for the cranes. I hadn’t known until I read her essay that New Mexico had left such an imprint on her young heart. I hadn’t known until she was asked to express it.

Getting outside may never be a modern kid’s first idea of what’s fun. There are so many more comfortable options, and most of them involve staring into the electronic fire. It’s our job as parents and mentors to come up with a better idea. The hitch is that we need to be ready to lead the way, to say, “No, we’re heading out, and you’re coming along.” We need to say it to ourselves almost as much as we need to say it to our children. We need to ask more of them, and of ourselves.

Julie Zickefoose draws inspiration for stories and pictures from Indigo Hill, the sanctuary she shares with Bill Thompson III, Phoebe, Liam, Chet Baker and countless other winged, scaled, furred, and slimed denizens. Her most recent book is The Bluebird Effect: Uncommon Bonds with Common Birds. She blogs at http://juliezickefoose.blogspot.com.This article was originally published in Bird Watcher's Digest and was brought to our attention by ParentMap contributor Jennifer Johnson, who also republished the essay on her blog, The Hiker Mama. Thanks to Julie for allowing us to republish it!