When our kids fail, it can feel like it’s our fault — that we as parents did something wrong. But when we ignore the cultural connotations of “failure” and examine what it actually means, that alters how we see our kids and ourselves.

“Failure is just when something doesn’t work out, either due to lack of effort or things just not going your way,” says Meghan Leahy, a certified parent coach, “Washington Post” columnist and mother of three daughters.

Of course, watching our kids struggle invokes our own vulnerabilities. That’s why Leahy suggests a shift in how we talk about failure from the get-go.

“If parents can think of themselves as failure facilitators, they can welcome the inevitable,” she says. “Failure plus the loving support of someone who deeply knows you and has your back leads to growth and resilience.”

Preschool (ages 3–5)

Being a preschooler is all about failure, says Leahy. Preschoolers fail at everything, from not sharing their toys to being unable to climb the rock wall at recess.

“Our job is to dance between allowing them to fail and making things work when we can,” says Leahy.

But that doesn’t mean making kids sit by themselves after they’ve made a mistake. Take, for example, when your child fails to control their temper and hits another kid.

“When a kid runs up and says, ‘Sarah hit me,’ [the adult] shouldn’t take over. [Instead the adult] should ask, ‘Did you say something to Sarah? How did you handle it?’ and give the kids an opportunity to stand up for themselves,” says Jessica Lahey, an educator and author of “The Gift of Failure.”

You want your child to be able to look another in the eye, address what they did wrong and solve their own issues, says Lahey. “[As parents] we want our kids to deal with failure when it happens. Yes, get disappointed and frustrated, but accept the fact that a mistake was made, regroup and figure out how to move forward. Parenting [around failure] is about asking, ‘What are you going to do next time?’”

For preschoolers, it’s particularly important to balance any reprimand related to failure with a reminder that you may be disappointed but you still love them.

“Failure plus shame equals kids shutting down and not trying new things,” says Leahy. “Try: ‘This hitting your baby brother isn’t working, but I still love you and you’re still my little boy.’”

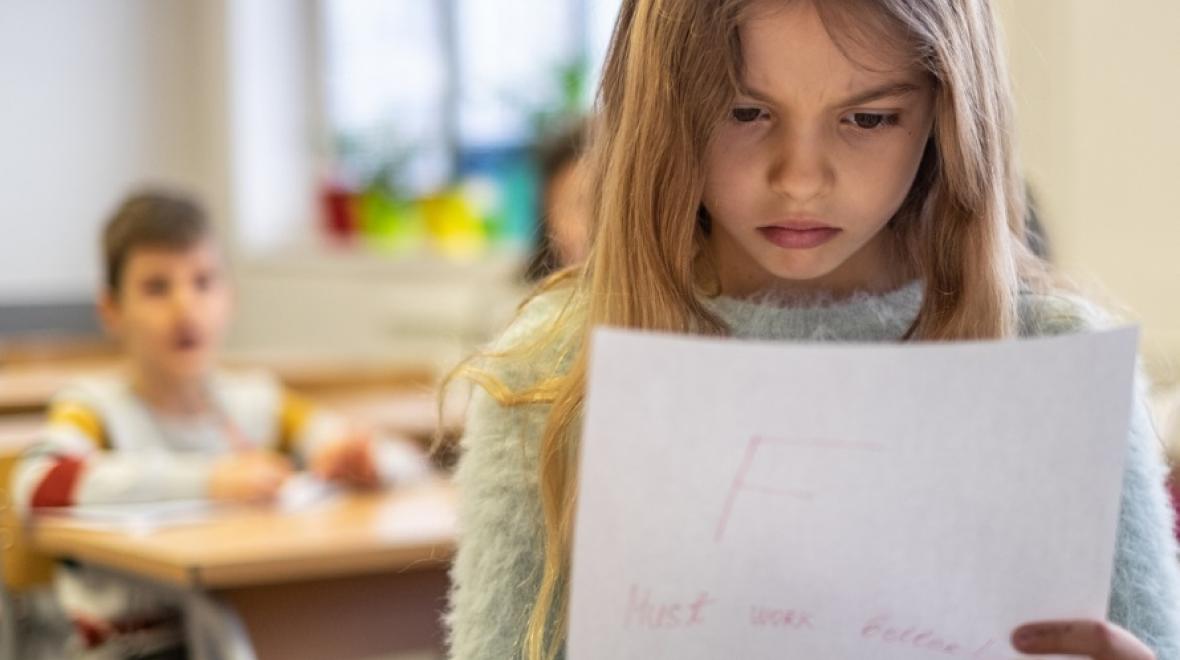

Elementary (ages 6–10)

In her 2007 book “Mindset,” psychologist Carol S. Dweck introduced research that showed students who believe their intelligence can be developed (a growth mindset) outperform students who believe their intelligence is fixed (a fixed mindset).

It may seem like an adult concept, but the third-graders in teacher Abby Mansfield’s class totally get growth v. fixed mindsets.

“This year, we made a poster for our door that says, ‘When I get stuck I will… ’ with all of their answers. We refer to it all the time,” says Mansfield, who teaches at St. John Catholic School in North Seattle. She’s also incorporated “my favorite mistake” into math lessons. When her students solve problems on their whiteboards and she spots a mistake, she gets really excited.

Failure plus shame equals kids shutting down and not trying new things.

“I say, ‘Yes! You made one of my favorite mistakes. See if you can find it and tell me why it’s one of my favorites,’” says Mansfield. The point is to make failure feel less bad and thus encourage a growth mindset among her students. The alternative — make kids feel bad when they mess up — often leads to them feeling that their intelligence is fixed so why even try?

Mansfield encourages parents to change their language around failure to eliminate the fear of failing and refocus on learning. For example, when your child says they aren’t good at math, add the word “yet,” as in “I’m not good at math yet.” Instead of praising grades, praise the strategy and effort behind the grades, even if the grades aren’t good: “Great effort. You must have worked really hard.”

Of course, failure at this age also involves plenty of social hurts, from failed friendships to feeling left out. Don’t expect your kid to have all the answers. If your child is shutting down, it’s your job to step in and say that’s enough, says Leahy. “If a friendship is fraught and the playdates are a disaster, you can cancel them,” says Leahy. “If the failure [of the friendship] is acute and hurting, take something away and load them up with your love.”

Tweens (ages 11–13)

By middle school, your child’s failures will likely take on higher stakes, from friendship fractures and social media mishaps to getting caught drinking or smoking pot. To help turn those failures into teachable moments, build your child’s autonomy in middle school, says Lahey. It pays off.

Nudge your child to take the lead instead of fixing problems for them, she adds. For example, if your child is having a problem in class, have your kid talk to their teacher (after you’ve let the teacher know your child needs to talk to them but is nervous. Then the teacher is aware a conversation is needed and will likely set up a low-stress situation to make it happen).

Helping grow your kid’s skills for self-advocacy helps them recover from a failure. It also helps them be less frustrated when things don’t go their way. Work by psychologist and researcher Wendy Grolnick shows that kids who have directive parents are less able to finish frustrating tasks when their parents aren’t around — bad news for an adult child who didn’t have the opportunity to fail when the stakes were low.

Sharing our own failures really helps, too, says Lahey. Tell them how it’s hard for you to receive negative feedback, and that it happened at work today and here’s what you did about it and how you felt. Showing your children that you fail, too, reminds them that you don’t expect perfection and, importantly, do accept them for who they are.

“It’s important that we love the child we have and not the child we wish we had, [and] that love isn’t based on a child’s performance,” says Lahey.

Teens (ages 14–18)

Teens are known for the eleventh-hour, 10 p.m. cry for help with the (unwritten) essay or forgotten homework assignment, says psychologist Laura Kastner. But sometimes, she says, the hero is the parent who doesn’t come to the rescue.

“Parents need to be resilient, too,” she says. “[We need to let] kids experience getting an F instead of saving them, so next time they’ll figure out a different way of approaching a paper or test.”

Kastner hears from parents who worry that if they let their kids fail a test, their children won’t get into college. But she believes it’s better for the kid to fail now rather than have no experience at solving problems for themselves when they’re actually in college.

“Struggle is how we learn,” says Kastner, co-author of the ParentMap-published book “Getting to Calm.” “I know it’s hard, but it’s a parent’s job to let the child feel their own feelings so they can learn.”

It’s natural that we’d become anxious when they do, but rescuing them to relieve both them and ourselves just isn’t worth it. Instead, “Say, ‘I love you and believe in you,’ then let them handle it themselves, with some emotional support from you. When they have a little victory and tell you about it, celebrate with them,” says Kastner.

Lahey experienced a related struggle with her younger son, who, at age 9, kept forgetting his homework. The day she didn’t bring it to him, a teacher told him he needed to create his own reminder strategy. “He came up with a checklist on the fridge,” Lahey recalls. “I tried suggesting ways for him to [jog his memory] long before this, but he needed [to create] his own strategy.” Now 14, he’s still making checklists.

Parenting, Lahey adds, isn’t about the small, everyday emergencies. “It’s about this long-haul vision of who you want your kid to be when they leave your home,” she says. Wrap your mind around that and you’re well on your way to letting them fail in small but important ways.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2018, and updated in October 2019.