If you’re as avid a reader of child development books as I am, you may recognize the subgenres that many of these books fall into. Perhaps you have a favorite — those that read like cookbooks with short chapters or the ones that are more like memoirs. Some are almost travel guide-like and still others dig deep into the science or history of the given topic.

Below are five newly released titles that neatly align with established categories to satisfy (or irritate) your parenting self-examination bug. Read on.

1. The evidence-based parenting tome

The Informed Parent

By Tara Haelle and Emily Willingham, Ph.D.

If you read only one book on this list, let this be it. The Informed Parent will influence what you take away from other parenting books. The authors, one a biologist and both science journalists, train you to be a critical reader; how to recognize your own confirmation bias (the opinion you bring to a situation); how to approach the results of studies (scientific or not); and how to effectively draw your own conclusions based on educated analysis.

This measured approach informs the content of The Informed Parent. The authors address parenting concerns for ages 0 through 4 by presenting the results of evidence-based studies that have been replicated and whose sample group was large enough to justify meaningful reporting. They cover topics such as prescription drug use in pregnancy, breastfeeding and formula, vaccines and gun ownership in the home, weighing the data for the reader and sharing what each of them did as mothers for their own children.

The combination of thorough research, reporting, accessible analysis and personal testimonials earns this book its title and then some; the authors have established a website with additional resources and links to the studies cited in the book.

Most reassuringly, the book includes an appendix titled “Making Sense of Scary Headlines,” which coaches the reader through questions for fraught topics. Whether you revere science or are skeptical of it, knowing how to discern data is a good skill to have, especially as a parent.

2. Free-range parenting

2. Free-range parenting

It’s OK to Go Up the Slide: Renegade Rules for Raising Confident and Creative Kids

By Heather Shumaker

Have you ever blurted out “stop!” to your child, then thought afterwards, “What was the big deal anyway? Why did I have to object to what she was doing?” Often our reactions are knee-jerk and not based on real threat or danger. If parents are constantly protecting their children from danger, bad news or disappointment, kids don’t learn to develop confidence, empathy and self-reliance.

That, at least, is the arguement presented by Heather Shumaker, a parenting consultant and author of It’s OK Not to Share. She wants to remind parents that kids need risk and self-direction in their lives in order to thrive. Let your kid go up the slide! she argues. If no one is harmed in the activity, what is the objection?

Personally, I agree with her chapters about sharing news disasters and unfair history with kids. NPR narrates my commute home every day with my 6-year-old son, and the news sometimes warrants some age-appropriate explanation about earthquakes, war and death. In having these converations, I teach my kid about community and resilience and, I hope, help him feel safe because he knows what's going on in the world.

Shumaker also suggests giving your child freedom to reject certain conventions. For example, your child doesn’t have to hug or kiss every relative or participate in every group activity. Forcing such convention, she says, teaches kids that their will and bodies are not their own to control.

Note: The book veers into more radical territory. Shumaker imagines a world where kids don’t start kindergarten until age 7 and where homework doesn’t start until high school. While her arguments are well-researched, they were a harder sell to me simply for the expense involved in keeping children home longer and so highly customizing their education.

Of course, such limitations are reader-dependent and overall, the book is excellent. The chapters contain scannable scenarios and suggested dialogue, as well as cues to “take off your adult lenses.” Shumaker’s writing is warm and accessible, and her advice worth considering.

3. The scannable pick-and-choose method

3. The scannable pick-and-choose method

Your Kid’s a Brat and It’s All Your Fault: Nip the Attitude in the Bud — From Toddler to Tween

By Elaine Rose Glickman

Sometimes we just want input for a specific behavior, rather than plodding through a whole book. We also want someone with authority and a sense of humor to guide us.

Glickman, a parenting advice columnist, author and rabbi, is the sassy, foul-mouthed friend you need. Her manner is appealing and her advice solid and loving (though expect a few swear words). Her philosophy is big picture: What kind of person do you ultimately hope your child to be and what kind of relationship do you want with them long-term? Glickman assumes you want to raise a competent, self-reliant, respectful, empathetic and participatory kid and proceeds accordingly when offering advice.

The book is arranged in short chapters addressing specific behavior such as “your kid whines” or “your kid has an obnoxious friend” or “your kid dresses like a prostitute.” At first I was put off by the bluntness but as I read deeper, I appreciate how Glickman doesn’t sugar-coat the tougher subjects and how she offers a way forward that is ultimately kind and forgiving. In my opinion, Seattle parents often get stuck in a bubble of niceness where we never comment on each other’s children and are convinced our own are exceptional. As such, I found Glickman’s manner refreshingly different.

In addition, Glickman provides prompts and sample dialogue for managing a child through each listed problem behavior, as well as suggested age-appropriate tasks and some funny real life Q&As from her advice column.

4. How Europeans do it (better, of course)

4. How Europeans do it (better, of course)

The Danish Way of Parenting

By Jessica Alexander and Iben Sandahl

A slew of recent parenting books written by American expats have trained us to expect a sophisticated mix of both memoir and guide. If you are expecting some European escapism, save your euros. The Danish Way of Parenting is the cool Northern cousin of this typically more “me”-focused genre.

Compared to authors like Pamela Druckerman, Adam Gopnik and Mei-Ling Hopgood, who write with the self-awareness of outsiders and the research and observation skills of journalist, The Danish Way of Parenting reads like a workbook. It was originally self-published in Europe as a how-to manual written by American expat mother Jessica Alexander and Danish therapist Iben Sandahl. The book caught the attention of American publishers, who are now publishing it in the States.

The short chapters and checklists outline a more authoritative style of parenting — information presented like gold, as if just discovered but mostly already known to Seattle readers familiar with John Gottman’s Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child. Both authors leave themselves mostly out of the book, making little use of their potentially rich source material (Alexander is an American married to a Dane who became a mother while living in Denmark).

One idea that stuck out to me: the concept of “hygge” applied to parenting. The Danish word “hygge” suggests creating a warm atmosphere and enjoying the good things in life with good people. This “coziness” is an essential part of Danish culture and parenting, write the authors. Unfortunately, the book’s checklist style and the absence of personal narrative didn’t impart much “hygge” to me. Rather, The Danish Way of Parenting left me cold.

5. New age parenting

5. New age parenting

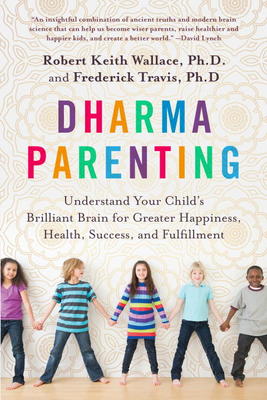

Dharma Parenting: Understand Your Child's Brilliant Brain for Greater Happiness, Health, Success, and Fulfillment

By Robert Keith Wallace, Ph.D., and Frederick Travis, Ph.D.

The word “dharma” coms the Sanskrit verb “dhri,” which means to “uphold” or “support.” Not surprisingly, it lends itself well to parenting philosophy. According to authors and neuroscientists Robert Keith Wallace and Frederick Travis, every child has a dharma, or path in life that supports personal growth, happiness, success and fulfillment. The tools presented in the book seek to identify and nurtery that dharma. Expect to learn about the Ayurvedic mind/body types of Vata, Pitta and Kapha and how to try transcendental meditation as a family.

The limits of this book are apparent right away. First, it is written for those who already walk the path of Eastern traditions and welcome a way to apply it to parenting. Personally, I try and avoid labeling my child early in life and to adhering to the kind of strict regimen presented in this book, which includes specific diet and behavioral methods. The authors also defer to the centuries-old history of Ayurveda, or “science of life,” which left something to be desired for a more analytical reader.

That said, there is still a lot here for parents interested in finding a structure to slow down and simplify their parenting. The emphasis on self-care as the parent is one I can’t argue with, and the authors offer mindfulness tips for both parent and child. The overarching theme of Dharma Parenting is the mind and body connection, protecting brain development and nurturing the whole family in the process.