On a recent summery evening, I was at a Seattle park with a friend, watching our 6- and 7-year-old boys bounce around a playground and talking about the way we used to play as kids. Lisa, a second-generation Korean-American, had spent much of her suburban Connecticut childhood playing with friends in the woods and climbing trees — as high as possible. “Like that,” she said, pointing to a nearby tree — 50 feet or so tall, spiked with branches up to the top.

“My mother didn’t have a clue,” she added.

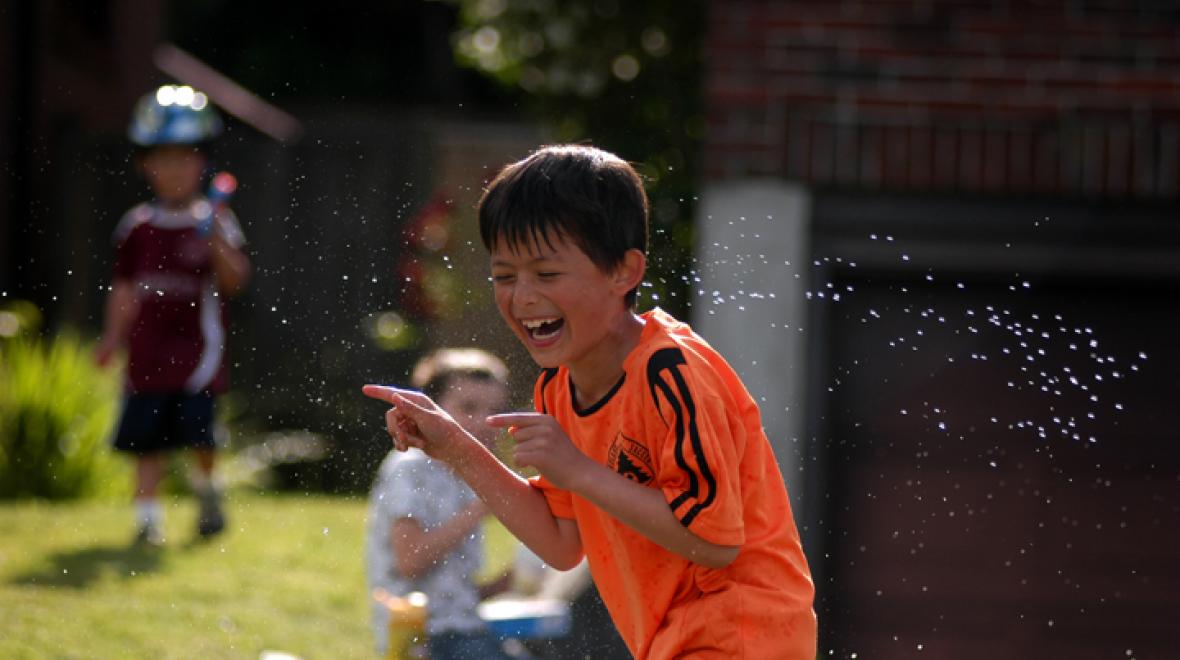

Child’s play has changed. Kids play outdoors less (up to half as much as their parents, according to several studies), roam less and are watched more. Child obesity is up, physical activity is down. Meanwhile, research piles up about the benefits of unstructured outdoor play — from physical strength and motor skills to improved executive function and emotional regulation to a lifelong connection with nature.

|

For more support and resources surrounding the youth mental health crisis, screen time and social media, and the importance of play, visit ParentMap’s Antidote for the Anxious Generation page. |

The decline of outdoor play isn’t news. We talk about it, and books have been written about it (the seminal text is Richard Louv’s 2005 "Last Child in the Woods"). And many of us Northwest parents are on it: We proudly hike and bike and camp, watching kids play for hours in the woods. But when we go old-school at home and kick our kids outside, they drift back in, complaining that there’s no one to play with and nothing to do. (And of course, many of us don’t have a place to kick our kids outside to.)

So, what’s a nature-loving, time-limited Puget Sound–area parent to do?

Mike Lanza has an explanation and an answer. The Silicon Valley dad of three and author of "Playborhood: Turn Your Neighborhood Into a Place for Play," a practical handbook for reactivating neighborhood-based play, acknowledges the many factors that have contributed to the decline of kid-generated outdoor play: busy schedules, two-career families, safety fears. But he also spotlights a reason that’s less talked about: competition.

“Decades ago, free play in neighborhoods was practically the only option for children looking for something to do. Today, though, children have the internet, lifelike video games, hundreds of television channels, dozens of structured activities and relentless marketing messages that draw them into malls and stores.”

And because kids (not surprisingly) want to play with other kids, it’s a downward spiral.

Neighborhoods, Lanza says, have got to get their game back.

“The big task,” he says, “is to make that neighborhood into a comfortable, warm, inviting place where parents can feel comfortable stepping back.”

Not all neighborhoods are equal, of course. Some are “playborhoods” by design, with sidewalks, front porches, quiet streets. Others have busy traffic, no sidewalks, crime. The good news: A grass-roots movement of city planners and play activists, as well as community-minded parents, are identifying steps that almost any neighborhood can take to promote connections and safe play. And summer, when outdoor fun is at its peak, is a great time to pilot a new play project.

1. Shut down the street

“Wheeee!” At 5:30 p.m. on a Friday, a crew of six kids, mounted on a motley collection of scooters, balance bikes, trikes and two-wheelers, takes turns flying down a short, gently sloped driveway and across the street.

It’s Play Streets night in this North Seattle neighborhood of close-in wood and brick houses. From about 5 to 8 p.m., a stretch of two usually busy blocks just off N. 85th Street, often used by cars as a shortcut to Green Lake, is shut down to vehicle traffic — marked by trash cans at one end and a barricade at the other.

In other words, for one night a week, a 2-year-old and his red balance bike can rule the road right there in front of his house, while his parents do something almost as rare: hang out.

“Most of the time, we’re standing around chatting, which is nice because we never get to do that,” says Wendy Law, a biomedical research administrator and mom of two who started this Play Street last fall. She had heard about the municipal program, which allows city residents to apply for a permit to shut down a non-arterial block for several hours as often as three times a week. After Law discussed it with neighbors at a neighborhood summer block party, the residents decided to try it.

Play Street smarts

Want to start a Play Street? Find out how to apply and tips for success.

Different neighbors take turns putting out and monitoring street barricades, an important role for a successful Play Street. On a warm evening, as many as 20 kids may be out riding bikes, playing soccer, drawing with chalk and playing games.

Law says that the weekly tradition is stitching closer bonds on a street where casual interactions can be infrequent, partly because of schedules and partly because of street design (traffic is busy, and front yards are small and not play-friendly).

Building neighborhood cohesion and, by proxy, safety, were among the goals of the city’s Play Streets initiative, which started as a Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) pilot project in 2014. “It’s important to have open spaces where we can play and get to know each other,” says Brian Henry, SDOT program development supervisor. And it’s equitable. “Play Streets is a great example because it can happen in nearly every neighborhood.”

The program is growing: In 2022, 103 Play Street permits where issued across Seattle. You can even apply for a Play Street permit for a street that you don’t live on; plus, it’s free to apply. (Find out how to apply here.)

Play Streets aren’t always successful, of course. Neighbors might not be on board, or it might not attract enough participants; on Law’s street they’ve dealt with irate drivers trying to pass through. But it is an example of a regular community ritual that can create informal play connections.

If your city doesn’t have an official program for closing streets to traffic (or you find Play Streets doesn’t work for you), set aside a regular time to gather in a yard or park. Summer is an ideal time to start a “Friday play day” that might extend through the school year.

An annual ritual can also pay off. Some Puget Sound neighborhoods band together for an annual progressive dinner, multi-family volleyball tournament or even a pig roast.

2. Be out there ... to bring the neighborhood in

Teddy McGlynn-Wright, who lives in Seattle’s Leschi neighborhood with his family, has a 4-year-old daughter, Charlie, who likes doing something that’s not done much anymore: popping in on neighbors.

The family — Teddy, wife Annie (a doctoral student in sociology), Charlie and toddler Theo — will be on a nightly walk, when Charlie will want to say hello. “It’s kind of uncomfortable,” says McGlynn-Wright with a laugh. “She’ll knock on neighbors’ doors, even though she is not usually an extrovert.” Sometimes, there’s no response. But other times, a kid comes out to play.

For McGlynn-Wright, who works in Seattle’s Office for Civil Rights and was an early supporter of Tiny Trees outdoor preschool, these small steps are important to build connections in their neighborhood. “It has so many hills … you’re really close to neighbors, but it feels like you’re really far away,” he says.

In "Playborhood," Lanza lists dozens of other ways that families can “be out there.” A biggie is to make the front yard, not the back, your hangout area. Adding fun features to the front yard, planting a garden in the parking strip and installing benches so people can sit all contribute to a neighborhood culture of spontaneous play.

Families that live in apartments might have a courtyard that can double as a play area. Linnea Westerlind, author of "Discovering Seattle Parks," says that alleys behind many busy urban streets can become the “new cul-de-sac.” Some housing developments, such as Snoqualmie Ridge or Tehaleh in Bonney Lake, actively incorporate (and market) elements of play-friendly design, including sidewalks, trails, playgrounds and regular events.

It can take time. Robin Bailey, a mom of four who lives in an Olympia neighborhood with few young families, has done many of the things Lanza suggests. But the response has been slow. “It’s a long game, not a short game,” she says.

3. Think outside the cardboard box: creative backyard fun

Visitors to Woodland Park Cooperative School in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood can be forgiven for confusing its outdoor play space with a junkyard. The small, hilly space, which adjoins Fremont Baptist Church, is strewn with ladders, tires, pallets, logs, plastic pipes and even an upside-down shopping cart. Natural materials also abound: tree trunk rounds, stumps, logs, garden boxes and a two-level sandbox with a pump at the top.

On a cloudy Thursday afternoon, a group of 3- and 4-year-olds joyously plays with all of it. One kid operates the pump, while another carefully walks across a log beam. One child hammers nails into scrap wood at the workbench while two others swing in unison on a metal swing set. The most fun is watching two small girls in pink dresses climb up a concrete slab built into the side of the yard, using a rope ladder to give them traction.

What is this magic? It’s loose parts: a staple concept of early childhood education that simply refers to materials without a clear use that prompt open-ended creative play (think of the proverbial cardboard box). Also, it’s risk.

The Woodland Park co-op’s loose parts tend to be bigger and more multi-use than those at many preschools — kids can climb, move and build with these parts. In essence, it’s a mini adventure playground. Or, as former lead preschool teacher Tom Hobson describes it, it’s a re-creation of “the natural free-play environment of the city: the vacant lot.”

Backyard tips from Teacher Tom

Want to make a state-of-the-art “loose parts” (a.k.a. junk) paradise in your backyard? Read Teacher Tom's tips!

Hobson — better known as “Teacher Tom” — writes a blog about the preschool that’s gained fame in early childhood education circles (he’s also published two books). He believes that kids are looking for risk, and if they don’t find it physically, they’ll create it in other ways.

“They tend to play so peacefully together in a place like this,” he says. “There are so many challenges other than getting into conflicts with each other.”

Places to tinker, connect and challenge themselves are important for kids, says Lanza of “Playborhood.”

Trampolines and other big investments have their roles as kid magnets, but the Woodland Park outdoor space offers a compelling example of how loose parts can also work in a yard. “Anybody can do this,” Hobson says. Families can adapt the principles according to kids’ ages. Natural loose parts, such as sand, water, stumps, logs and edible plants, create variety and adventure. Loose cardboard boxes and crates add building materials. Scrap wood and tools (with training) spark fort building. A pile of dirt with spades engages kids long past preschool age. (See Mike Lanza’s book "Playborhood" for an example of an epic front yard that combines loose parts with a trampoline, two-story fort, “stream,” and more.)

4. Slow down and step back

Angela Hanscom, pediatric occupational therapist, author of "Balanced and Barefoot," and founder of TimberNook nature programs, writes about not rushing kids into play. “It sometimes takes a good 45 minutes before children get into ‘deep play,’” she writes. “This is the sort of play where children start creating their own games and their own rules.”

Slowing down doesn’t take special technology, but it’s a mind-set that doesn’t seem to fit modern culture. (My specialty is rushing through a hike.) But taking extra time is a good fit for summer and for neighborhood play.

Ever heard the phrase “hummingbird parenting”? It means being around but zooming in only when really needed — for instance, freeing ourselves to work on our badminton game as the kids make up a new version of “kick the can.” And it’s what I’ll be doing this summer.

9 ways to prompt outdoor play

|

Editor's note: This article was originally published in 2017 and updated for 2022.