The Czech children’s opera Brundibár, staged in two performances on March 22 and 23 by Music of Remembrance at Seattle Children’s Theatre, is an uplifting story with a jaunty score where good triumphs over evil — but which carries a heavy history from the Holocaust.

This requires some explanation: First, the opera itself. Brundibár, composed in 1938 during the rise of Nazi Germany and set in a shtetl-like setting, is the tale of Pepicek and Aninku, a brother and sister trying to raise money to buy milk for their sick mother. Inspired by seeing people throwing coins into the hat of the village organ grinder (Brundibár) the duo decide to sing for their own coins. But greedy Brundibár (“bumblebee” in Czech) drowns out the children’s voices.

Eventually, a trio of friendly animals help rally the village children to create a powerful chorus: the villagers hear the children’s songs and soon Pepicek’s cap is full of coins. Nasty Brundibár tries to run away with the money but is quickly defeated. The children celebrate their victory and the choir sings of friendship and support.

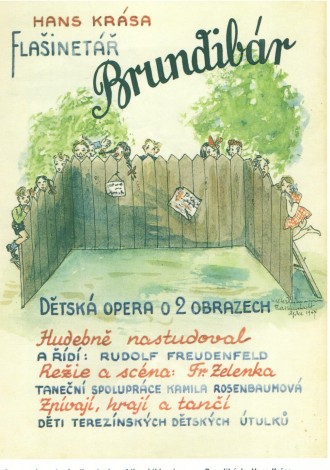

Now, the historical context. Just before Brundibár premiered in 1942 at the Jewish boys’ orphanage in Prague, the composer, Hans Krása, was arrested and sent to Theresienstadt, or Terezín, the “model ghetto” that served as a hub for transport to the Nazi death camps.

The conductor of the premiere performances smuggled the score with him when he and the boys from the orphanage were also sent to Terezín. Ultimately, the opera was performed 55 times by casts of children in Terezin — casts that needed constant replenishing as the young singers were transported to death camps.

Brundibár the bully became an allegory for Hitler (children playing the role even wore a Hitler mustache). The Nazis showed Brundibar to outsiders, including the International Red Cross, as part of the Third Reich propaganda to mask the ghetto prison and the camps.

“Brundibár is really about the power of music to make miracles happen,” says Mina Miller, artistic director of the Seattle-based organization Music of Remembrance, which presents musical performances, educational activities, recordings and commissions of new works to remember Holocaust musicians and their art. “It’s a very accessible performance about confronting evil.”

"When we sang, we forgot where we were"

For the Seattle production, Northwest Boychoir’s music director, Joseph Crnko, will conduct an all-child cast, featuring many singers from the Boychoir and Vocalpoint! (a co-ed choral group of high schoolers from across the Puget Sound).

The Seattle production will include a Terezín Revue, highlighting the role music and art played in camp life. For example, the revue will include some short readings from a secret magazine a group of boys created at Terezín, as well as the anthem they sang when meeting each week to read aloud from their creations.

The Seattle performances also feature the only remaining survivor from the Terezín casts, Ela Stein Weissberger, who has worked to preserve Brundibár and its legacy. Weissberger was 11 when she was sent to Terezin in 1942, a time she writes about in her book The Cat with the Yellow Star.

In all 55 performances she sang the role of the Cat, one of the helpful animals. Seattle Brundibár cast members will have a brief Q&A with Weissberger onstage about her experiences performing the opera. Evidently, Weissberger didn’t share the fate of other children from Brundibár because a Nazi officer didn’t want to lose Ela’s mother as a worker in his garden.

“When we sang, we forgot where we were,” recalls Weissberger. “We forgot hunger, we forgot all the troubles that we had to go through.”

“When we sang, we forgot where we were,” recalls Weissberger. “We forgot hunger, we forgot all the troubles that we had to go through.”

Don’t be surprised if Weissberger joins the children onstage for the final victory chorus:

“When a bully’s near, tell him you’re not afraid! You’ll see him fade away! Friends will volunteer! And bullies disappear! Tyrants come along, but you just wait and see! They topple one, two, three! Our friends make us strong! And so we end our song!”

Talking about the Holocaust

The big questions for parents: What's an appropriate age for kids be to see Brundibár? To learn about and discuss the Holocaust?

Miller says the show is appropriate for children of all ages; there is no Holocaust imagery. The Seattle show is an English adaptation of the Brundibár staged in Terezín, based on a libretto by award-winning playwright Tony Kushner. When Kushner’s production was performed in New York City, the recommended age was 8 and up.

Certainly, the opera can serve as an introduction to parent-child discussions about the Holocaust, though the performance may not prompt your child to ask questions unless you bring it up. If you do want to broach the topic, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum has a slew of resources. (The museum generally does not recommend students younger than middle school age study the Holocaust in school; one museum exhibit is geared toward students as young as fourth grade).

Judith Vandervelde, senior educator at the London Jewish Museum, has run seminars on how to talk to children about the Holocaust. "The philosophy behind teaching young children about the Holocaust is that you take them up to the gates of Auschwitz and no further,” Vandervelde has said.

In a 2011 article with the Jewish Chronicle online, she advised parents to only go as far as they feel their child can handle. "It depends on the child's maturity, their family background and their experiences of death. Be led by them and answer questions as simply as possible. If they want more, they will ask."