Divorce Is The Worst is the book you should bravely buy for your divorcing friend. You could leave it in your friend’s car after you go out for tea with him. You could go by her house with a casserole (divorce is like a death; we need the casseroles), and in the bag with the lasagna, the wine, the bread, the flowers, the dessert, there could be — wait, one more thing at the bottom, here it is — this book, Divorce Is the Worst, for her to read with her kids.

You might feel awkward. You will be addressing the fact that the divorce affects her children; you’ll be calling attention to the fact that, indeed, for your friend’s children divorce is — if not the worst — at the very least not great. But you’re not really calling attention; your friend’s attention is already there. She knows. He knows. Your friend would like to address the suffering of her children caused by the divorce. She is trying already to do just that, no doubt. But sometimes they don’t quite know how.

The thing to do — the thing children need during divorce like living things need oxygen — is to fully acknowledge their feelings of loss. And while we divorcing parents want to do anything needed to help our children, we are human, and to be human means not wanting to look at your child in the eyes and see that your choices have caused suffering for your child who you love to the moon and back. To be human means wanting to change the subject when the subject is this hard.

I know this because I am divorced. Our divorce caused my two children to suffer. My decision brought fresh pain into their lives, along with a parenting schedule and little red rolling suitcases that we jokingly and dead seriously have called The Divorce Suitcases since they were purchased by their father nearly 12 years ago. Like most divorced parents, I strove to do the best I could to create an amicable divorce and a brave new life of coparenting. And like most parents, I have a deep aversion to my children’s unhappiness. I have wanted to acknowledge their suffering, but I have also wanted, at times, to pretend it wasn’t there.

Sometimes we feel so guilty about the divorce that we can hardly bear to witness our children’s feelings of loss. A picture book — this picture book, Divorce Is the Worst — can help us in those moments.

Plus, sometimes I didn’t know how to acknowledge it. When I went through the court-ordered “What About the Children?” class that all divorcing parents in Washington state went through in 2004, I was given a reading list, and on it was just one book I could read with my preteen daughter (a very good book called It's Not the End of the World by the fabulous Judy Blume) and a pretty good book about dinosaurs divorcing I could read with my 5-year-old. The trouble is we are not dinosaurs. We are people, and we needed a book about a real kid going through a real human divorce.

One parenting book that was extremely helpful to me during my divorce was the book Helping Children Cope with Divorce by Edward Teyber. In Helping Children Cope with Divorce, Teyber makes the point that divorcing parents often allow their guilt about the divorce interfere with their parenting. He urges parents to do whatever they can to release their own guilt so that they can remain steady at the parenting helm. In fact, it’s often our own guilt as parents that prevents us from offering our children that chance to really have their feelings of loss heard. Sometimes we feel so guilty about the divorce that we can hardly bear to witness our children’s feelings of loss. A picture book — this picture book, Divorce Is the Worst — can help us in those moments. Staring at the pages of this beautiful book together, parent and child can find an easier way to talk about divorce.

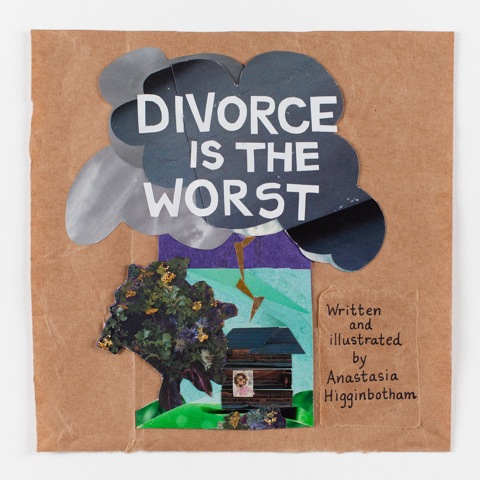

Divorce Is the Worst (from Feminist Press) is the book I want to turn back time and read with my 5-year-old on my lap. Divorce Is the Worst by Anastasia Higginbotham is a book that allows children to see themselves and their many feelings realistically portrayed. One of the beautiful aspects of this book is that the protagonist is not identifiable as any specific race or gender but is an “everychild” with whom any child can identify. The feelings of displacement and loss and longing and guilt and anger common to the child whose parents are divorcing are brought to life exquisitely in these pages.

I received my advanced copy of the book a month or so ago and I left it out in the living room. My once 5-year-old daughter is a high school student now, but she found the book and read it. She later showed me her favorite pages, which were many.

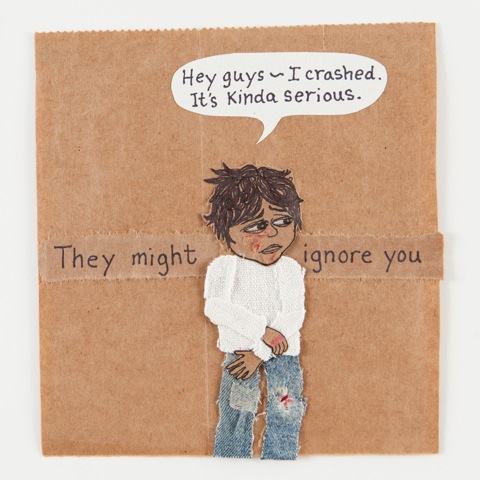

She said the part when the child falls off the bike was almost unbearably sad.

“Too sad?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “The right amount of sad.”

Theo Nestor: How did you decide what to put in and what to leave out of Divorce Is The Worst?

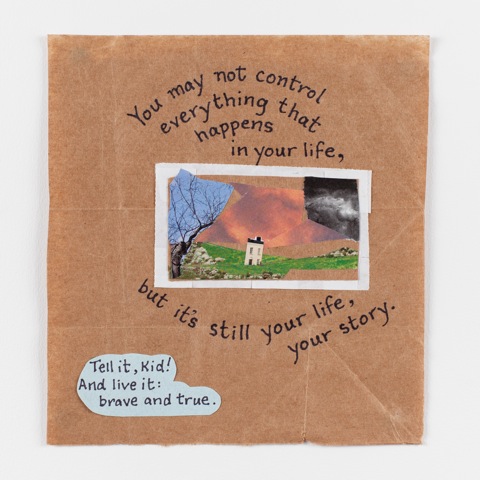

Anastasia Higginbotham: That whole “It’s for the best” thing bugs me and, one day, the obvious retort — “It’s the worst” — popped to mind. The rest of the book came together in batches. There would be the announcement and then a flood of emotional reactions, one after the other, actually knocking the child over onto the ground. I knew I had to walk with the reader through the inevitable changes of divorce and show how feelings get misplaced. So, a zipper that won’t zip feels like the world is ending, but a bloody bicycle crash (which was originally going to last for six pages instead of two) is ho-hum. I wanted the injury of the parents’ separation to show. I wanted that kid broken and still moving forward, trying to understand and cope, the way kids do. And I experimented with different ways of showing how the child contends with the parents’ emotionally loaded reasons for separating — which can easily intrude on a child’s process. I had to make the reasons disappear to allow the child’s mind to get quiet enough to hear their own inner voice instead. But the end I did not know about until I got there. The words came to me and made me cry, and I knew I had done it. I had solved the riddle of what had been hurting me all this time.

Anastasia Higginbotham: That whole “It’s for the best” thing bugs me and, one day, the obvious retort — “It’s the worst” — popped to mind. The rest of the book came together in batches. There would be the announcement and then a flood of emotional reactions, one after the other, actually knocking the child over onto the ground. I knew I had to walk with the reader through the inevitable changes of divorce and show how feelings get misplaced. So, a zipper that won’t zip feels like the world is ending, but a bloody bicycle crash (which was originally going to last for six pages instead of two) is ho-hum. I wanted the injury of the parents’ separation to show. I wanted that kid broken and still moving forward, trying to understand and cope, the way kids do. And I experimented with different ways of showing how the child contends with the parents’ emotionally loaded reasons for separating — which can easily intrude on a child’s process. I had to make the reasons disappear to allow the child’s mind to get quiet enough to hear their own inner voice instead. But the end I did not know about until I got there. The words came to me and made me cry, and I knew I had done it. I had solved the riddle of what had been hurting me all this time.

Nestor: What inspired the book?

Higginbotham: My parents’ separation when I was 14 was a complete shock and a heartbreak. They didn’t want it to affect us and insisted that it shouldn’t. They actually said those words out loud: “Don’t let this affect you.” Look at me now, right? Almost 30 years later. I wrote and drew my first divorce book for our family when I was 18 and my dad had recently remarried. It was in Dr. Suess cadence and had lots of jokes: “All the relatives when told felt that nothing was worse — it’s like Mary and Joseph were getting divorced!” It was also very forgiving, very focused on the positives. I was still attached to our original family. We were the 5A’s — five kids all named A names and dressed in matching outfits that our mother made, with this scary dad we adored who wanted us to play piano and be stars. Like the von Trapps. But the divorce did set us all free from those roles, so there was a grace borne out of disgrace. It was like, If Mom and Dad can fail and be disappointing and we all still love them, then WE can fail and be disappointing and they will still love us! But instead of failing, we became brazenly, unapologetically ourselves, and free.

Nestor: Tell us about your creative process. I'm very curious if you write the book, then come up with the illustrations and also how you chose the materials.

Higginbotham: I wrote it and then made the illustrations. At first, the collages were huge, 8x10, collaged from top to bottom, side to side, all the way to the corners. But it was too complicated. I needed to tell it more simply, just a patch of sky and a child whose posture says everything. That’s when I realized I could leave out a lot of the words I’d written, too. I found my way to this square of brown grocery bag paper — which I am in love with for its toughness, its prettiness and its usefulness. I have never been able to recycle (let alone toss) a clean brown paper bag. It would be like putting a warm coat in the trash, or a hammer. And the fabric is cherished family stuff like my grandparents’ cloth napkins and my son’s first, smallest Batman underpants.

Higginbotham: I wrote it and then made the illustrations. At first, the collages were huge, 8x10, collaged from top to bottom, side to side, all the way to the corners. But it was too complicated. I needed to tell it more simply, just a patch of sky and a child whose posture says everything. That’s when I realized I could leave out a lot of the words I’d written, too. I found my way to this square of brown grocery bag paper — which I am in love with for its toughness, its prettiness and its usefulness. I have never been able to recycle (let alone toss) a clean brown paper bag. It would be like putting a warm coat in the trash, or a hammer. And the fabric is cherished family stuff like my grandparents’ cloth napkins and my son’s first, smallest Batman underpants.

Nestor: How does writing and creating fit into your everyday life?

Higginbotham: Writing and creating are how I internalize everything that is happening. It’s how I convey what I’m learning or trying to learn. Essays are not as satisfying or honest as something with pictures that I wrote by hand. Love letters are very satisfying. It’s how I let people know that I am thinking about them and want to really know them. I made a big poster with my son when we were getting ready to stop nursing. It was of all his older cousins who nursed for a few months or a year or whatever, and then stopped nursing. He drew in all the faces and was on there as longest nurser of them all at almost 3 years old. Other people’s drawings and handwriting are alive to me too. It’s that person, in another form as a scrawl on a Post-it, and it makes me love that Post-it.

Nestor: What writers and artists inspire you?

Higginbotham: Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estes, Lynda Barry, Grandma Moses, Faith Ringgold, Mattie Lou O’Kelley, Romare Beardon, Matt Groening, Gloria Steinem, Maxine Hong Kingston, Patricia Polacco, Ani Difranco, Tomie dePaola, Mickalene Thomas, Swoon, Mr. Rogers, my friend Sharon Wyse, and my mother.

Nestor: I also really love Lynda Barry, Maxine Hong Kingston, and Gloria Steinem! Tell us a little about the series this book will be a part of.

Higginbotham: Divorce is the first topic in my Ordinary Terrible Things series to be published by the Feminist Press, which will also address death, sex, bullying related to perceived gender identity, sexual abuse within the family, and chronic illness compounded by racism. I also want to do adoption and school trauma. Each book will feature a different kid in a different familial arrangement. Each book will zero in on that kid at a time of complete emotional chaos or unraveling and then walk with them through one small piece of that confusion, to get them to that one thread of awareness and understanding of their own worth that makes them want to hold onto the thread for dear life (their soul’s life), as they go on to find another thread, and another, and another, and can start weaving it into something their very own. Crazy looking and scrappy and beautiful and theirs.

Anastasia Higginbotham has worked in New York City for 20 years as a speechwriter for social justice organizations. Her essays have appeared in Ms., Bitch, Glamour, The Sun, The Women’s Review of Books, and in various anthologies, including Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape. She is a 2015 Hedgebrook Fellow. Follow Anastasia on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.