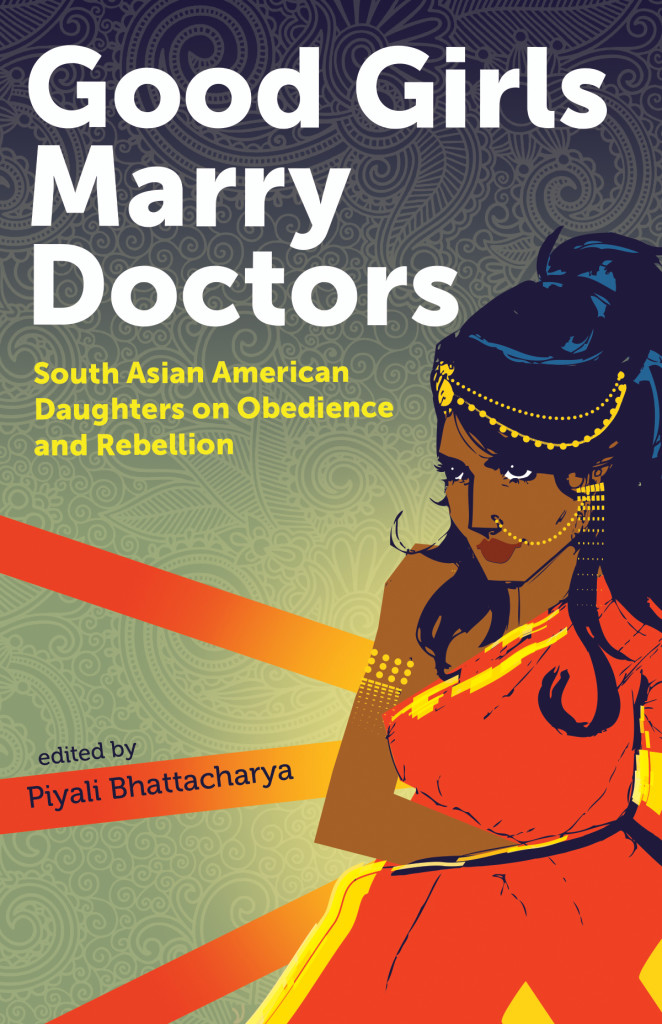

“Like a sleepover, the book’s stories made it OK to reach for another person’s hand in the dark … and put a name to that moment of embrace when your hands touched,” Piyali Bhattacharya told the intimate room at dusk. About 50 people gathered Tuesday at The Elliott Bay Book Company to hear Bhattacharya read from an anthology of essays she edited: Good Girls Marry Doctors: South Asian American Daughters on Obedience and Rebellion.

“Like a sleepover, the book’s stories made it OK to reach for another person’s hand in the dark … and put a name to that moment of embrace when your hands touched,” Piyali Bhattacharya told the intimate room at dusk. About 50 people gathered Tuesday at The Elliott Bay Book Company to hear Bhattacharya read from an anthology of essays she edited: Good Girls Marry Doctors: South Asian American Daughters on Obedience and Rebellion.

The book, as Bhattacharya told the room, is “for and by South Asian women.” It explores what it means to be a South Asian woman in America today; central to its message is each female author’s relationship to her parents and community.

This idea resonates with me as I reflect upon my identity as a Singaporean with Indian immigrant parents who is raising an American child in Seattle. As a new parent, I often wonder how my son will relate to his South Asian roots as dictated by his skin color, when I have only recently started grappling with mine. How will that relationship change as he grows in a divided America?

Many of the authors Bhattacharya worked with told her they agonized over “what their moms would say when they read their stories.” These are grown women, some with grown daughters of their own, but their concerns don’t surprise Bhattacharya. She addresses this concept of the South Asian “Good Girl” in the introduction of her book:

“Success is a funny thing for us Good Girls. Most of us have been schooled by our parents and our communities since we were children not only to strive for but also to desire a certain kind of life: academic rigor, followed by a well-respected job, but within a career which might allow us to stay at home and raise our children once we marry a hard-working, respectful and high-earning Desi [South Asian] man. Speaking of children, we should raise ours the way we were raised: with a good understanding of the language and ethnic traditions that were handed down to us by our parents.”

I’ve witnessed subtle variations of the same concept of the Good Girl among Diaspora South Asians in the countries where I’ve lived: Singapore, Britain and now America. It’s one we acknowledge with a wry smile, but can never wholly express aloud.

Immigrant parents have long been caricatured — further vilified by stereotypes brought on by the harsh rigor of “tiger” parenting — but it’s rare to read about childhood experiences as written by the kids involved, particularly the experiences of first-generation South Asian American women.

The stories in Good Girls Marry Doctors explore what happens when Good Girls don’t comply — when they decide not to marry, when they speak out against traditions, when they don’t attain “a well-respected job,” when they don't have children. These concepts may seem pedestrian to other communities, but speaking up against the status quo is brave in the South Asian Good Girls community. In my experience, the fear of bringing shame or dishonor to our families runs so deep, we hide our secrets –– of feeling suffocated, of rebellion, of abuse.

Good Girls Marry Doctors explores these themes and more. In the essay “Daughter of Mine,” author Meghna Chandra shares the agonizing moments between realizing she may be pregnant and going for an ultrasound with her mother, who doesn’t know about the pregnancy. In “The Fantasy of Normative Motherhood,” a queer Bangladeshi-American mother discusses the societal pressure imposed on women to want children, and in “Cost of Grief” — an essay that will remain with me forever — Tanzila Ahmed spends her mother’s funeral reflecting on how her mom was the glue between herself and her abusive father.

The Seattle metro area has experienced a 173 percent jump in its South Asian population in the decade leading up to 2012.

The book contains 27 essays though Bhattacharya received a total of 70; she says many authors withdrew their work out of fear of negative repercussions. Indeed, some of the published essays have caused rifts within families and, in a few instances, severed ties completely, says Bhattacharya. Many of the featured authors wrote their essays in secret, and some haven’t revealed their contributions to their families.

In reading Good Girls Marry Doctors, I saw vivid parallels between my experiences and those of my Diaspora peers. I found a solidarity with these strangers, a connection that ran deeper than with some people I’ve known my whole life. “They know,” I kept thinking, as I devoured each page. “They know what it’s like to walk in at least two worlds at any given time.”

The courage shown by these writers has had extraordinary ripple effects in creating a stronger community of South Asian American women in America, adds Bhattacharya. That community has rapidly grown in recent years; the Seattle metro area has experienced a 173 percent jump in its South Asian population in the decade leading up to 2012.

I saw this first-hand at the Elliott Bay reading; the majority of the crowd was female and half were visibly South Asian. Throughout Bhattacharya’s 90-minute reading, I saw fervent nods of recognition from those sitting alongside me.

Bhattacharya credits her parents’ strong support of her work as inspiration for her “hold[ing] space for the women who wrote for the book" and to "continue fighting for them.” Her goal, she says, is to insure the success of the next generation of South Asians and that, she says, means “telling our stories … and bringing our activism home.”