.jpg) Anyone who has ever raised a t(w)een recognizes the inverse relationship between the age of the child and the influence adults have over that child. When kids get older, instead of relying on adult founts of wisdom, to whom do they increasingly turn? Their peers.

Anyone who has ever raised a t(w)een recognizes the inverse relationship between the age of the child and the influence adults have over that child. When kids get older, instead of relying on adult founts of wisdom, to whom do they increasingly turn? Their peers.

Now, savvy educators are tapping into peer wisdom by encouraging adolescents to open up and support each other. Even better, these peer mentors are not doing this on the fringes of the school day, in bathrooms, at lunch or after school.

Teens are helping other teens and getting academic credit for it. And in the process, they just might be helping themselves.

The young and the restless

“Be young once or be immature forever,” says Adriana Galván, Ph.D., an adolescent-brain researcher at UCLA, whose studies have determined that trial and error is necessary in order for brain maturity to occur. At the same time, changes in the developing adolescent brain make teens particularly receptive to each other. When they are considering taking a risk, they’ll often turn to a friend for advice. That’s why it helps if the friend has training.

“Grown-ups have an agenda. Peers with experience don’t,” say the peer mentors at Seattle’s Northwest School (NWS). The school’s peer mentor program is a yearlong class for juniors and seniors that engages students in conversations about issues they face, and trains them to be resources to peers and younger students. Ellen Taussig, one of the school’s founders, developed the program based on a model she found at a Quaker school, after foreseeing the importance the program could have on leadership development and the school community.

At the beginning of the school year, each peer mentor is assigned a group of ninth-grade mentees to reach out to, but the mentors are also available to provide support to any student who asks for it.

Peer mentors say the biggest issues their peers struggle with involve friends, stress, gender identity and how to have healthy relationships. During the year, they participate in “text-ins,” in which students can anonymously pose their questions and receive support from a roomful of peer mentors. Peer mentors also facilitate activities and conversations across grade levels and play important roles in the nine-grade health program. Once a year, peer mentors participate in a “fishbowl,” in which they frankly answer questions from parents about topics such as drugs, alcohol, social media, sex and teenage life.

Be cool. Go to school

Lori Markowitz runs Youth Ambassadors, a peer truancy/dropout prevention program. Having a school-based program is crucial, she says, as is giving peer mentors academic credit for their efforts.

Markowitz’s model was born out of Seattle’s 2008 Seeds of Compassion conference, at which she convened with a diverse group of students to define what compassion meant to them. “Part of being compassionate is understanding ‘the other,’” Markowitz says. Once the conference was over, the students begged her to continue the program.

The Youth Ambassadors program caught the attention of the King County Prosecutor’s Office, which asked the ambassadors to speak at truancy workshops. Eventually, the Youth Ambassador program was brought to individual schools.

The program has received local and national recognition, including from America’s Promise Alliance, a group founded by Gen. Colin Powell to prevent kids from dropping out of high school.

Now administered by the Seattle Indian Health Board, the program operates at Cleveland and Nathan Hale high schools, and recently took root at Denny Middle School and Roxhill and Concord elementary schools. Each school program has the common agenda of empowering older students to support younger ones.

We are the stories we tell

Scriber Lake High School English teacher Marjie Bowker has found a different way to use class time for teen peer mentoring — by partnering with Seattle writer Ingrid Ricks to teach narrative writing through personal storytelling.

Scriber Lake High School English teacher Marjie Bowker has found a different way to use class time for teen peer mentoring — by partnering with Seattle writer Ingrid Ricks to teach narrative writing through personal storytelling.

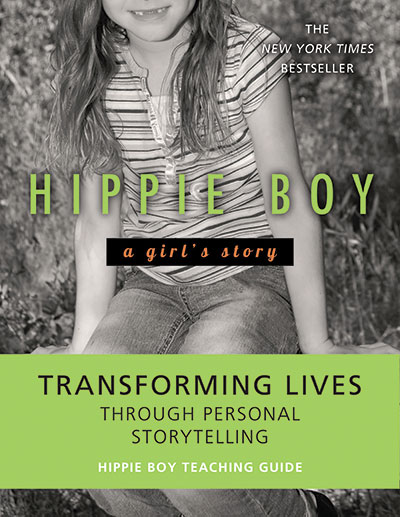

Ricks is the author of the memoir Hippie Boy, which tells of her escape from an abusive stepfather. A visit by Ricks to Bowker’s classroom led to a powerful collaboration. Over the past two years, this dynamic duo has helped students write and publish their stories, many of which are collected in the anthologies We Are Absolutely Not Okay and You’ve Got It All Wrong.

“A big issue is how to make high school relevant to students,” Ricks says. “Every teen has something they struggle with. By giving voice to it, you give them power.”

Bowker says her students, many of whom have suffered adverse childhood experiences, are excited to write their stories. As their peers watch these stories take shape, they form a support group.

“Our school community has completely changed in the past two years,” says Bowker. “We write our own stories now.”

Bowker has developed a curriculum for teaching Hippie Boy, and Ricks is at work on a primer for how to publish student anthologies.

There’s a lack of meaningful ways to engage teens at school, they say, and, judging from the growing interest they are seeing from around the country, the power of personal storytelling may be a way to fill that void.

Bowker says of the project, which has generated the most student interest she’s seen in 18 years of teaching: “We’ve hit on a way to change the course of their lives.”