Photo:

Eliza Truitt

Editor's note: This article was sponsored by the Giddens School.

The events of 2020 have opened a lot of eyes to the inequity in a society many of us were raised to believe was mostly fair. This growing awareness has, in turn, led many parents to question the way our children learn. How do we help our kids develop empathy instead of fear of people who are different from them? How can we avoid indoctrinating our children into racist systems? How can we teach them to recognize and resist bias in themselves and others? For many parents, these are new questions, or questions that have taken on renewed urgency.

Morva McDonald, Ph.D., has been grappling with these questions for years, both as a parent of two children and as the head of school at Giddens School. Giddens School is an independent school in Seattle's Rainier Valley serving children in preschool–grade 5 where 20 percent of the annual budget is committed to financial aid. Giddens School has always focused on social and emotional learning with a commitment to justice. Today, it is one of the most diverse independent schools in the area, enrolling 40 percent students of color.

Justice is interdisciplinary

McDonald credits founder Huda Giddens for establishing school values that were extremely progressive for the early 1970s. Since that time, the school has evolved in response to a growing understanding of social justice. This included moving from the Laurelhurst neighborhood of Seattle to the Central District in the 1980s.

“We were the first independent school south of Jackson. Geography matters — in who shows up at your door, who you see when you look around in your neighborhood, who you feel accountable to,” says McDonald.

More recently, the school developed a curriculum they call SPARK — an interdisciplinary, project-based set of units at each grade level combining science, social studies and social justice. Every two years, these units are evaluated and updated to reflect new learning.

“Last year, one of the units for our fourth- and fifth-graders was on oppression and resistance. They focused on things like how the Underground Railroad was used as a tool of resistance. Who was involved? What politics needed to be incorporated to create such a system? And how are economics involved?” says Brenda Cram, Giddens’ associate head of school.

SPARK units are not limited to social studies classes. For example, a science unit about the straightening of the Duwamish River can integrate politics, history and the impacts on people living in communities alongside the river.

“Anything that is specific to a particular project has a comprehensive, holistic impact on the world that is broader than just the project itself,” says McDonald. “Sometimes our classrooms feel slow in terms of content because we’re spending time really talking with kids about their emotions. But we want to help them get smarter across all three areas: academic content, social-emotional work and social justice work.”

It’s never too early to talk about justice

“Conversations about police brutality in some communities can be seen as not really developmentally appropriate for fourth- or fifth-graders. In a diverse community, I have to think about the different ways that people are experiencing that topic. To ignore it would obscure their reality as children. There are new ways developing to talk about the world that are developmentally appropriate and sometimes we’re pushing that developmental boundary,” says McDonald.

Children can be introduced to concepts of inclusion and equity even at the preschool level in standard units of study, such as “sound.” Cram says that in addition to typical exercises such as making musical instruments, classrooms can ask, “How is sound inclusive? How can we use sound for someone who doesn’t hear? Vibration, and the fact that you can feel sound as well as hear it then comes into the conversation.”

It’s not just a theory

“There’s the idea that proximity will help us make change. But it’s not enough. What you want to help kids develop is an understanding that has both empathy towards somebody’s experience of marginalization in the world and some level of agency and accountability related to it,” says McDonald.

Kids first need to notice how their experiences are the same or different from those of their friends. Students may play at classmates’ houses that look very different from their own, or spend school holidays in very different ways. The next step is questioning their responsibility to those differences. McDonald cites the example of her son riding the bus with a friend. Her son, who is white, noticed that people on the bus interacted differently with his friend, who is black. “So, he has to ask, do I ignore that? Do I talk about it? Do I need to stand up for him?” she says.

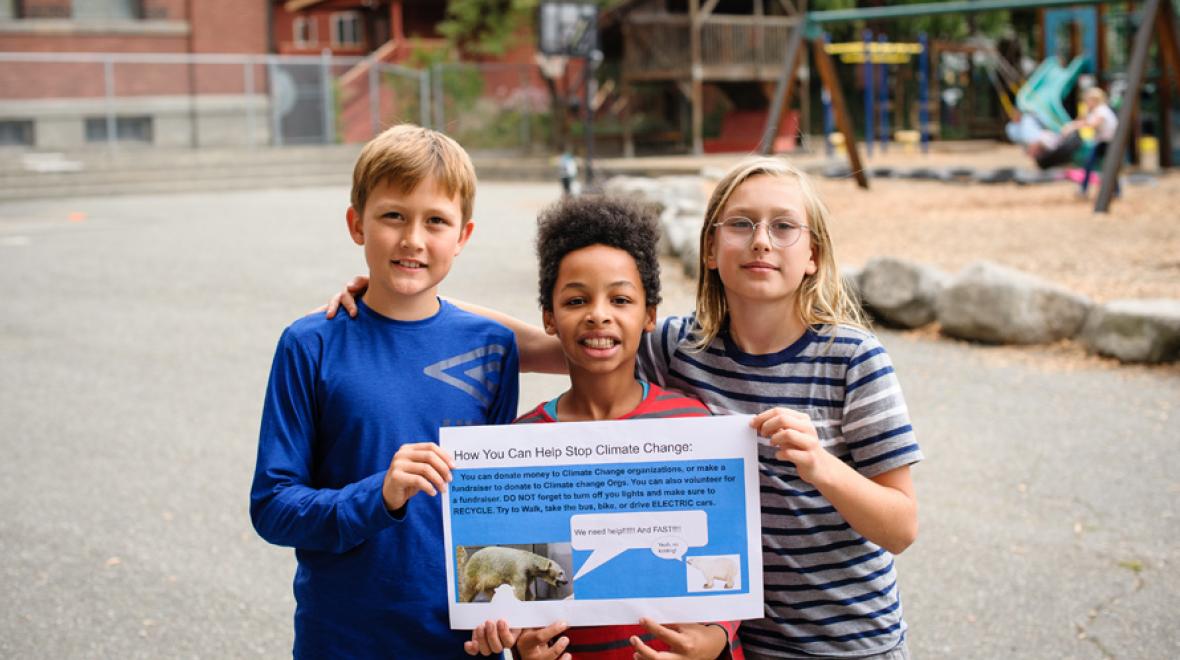

A curriculum that allows children to place events in a societal context combined with social-emotional learning that builds empathy helps children begin to ask these questions. It’s also important that children have tools to act against injustice. Giddens School’s annual student march on MLK Day “is a celebration of the work of Dr. Martin Luther King, but it’s also a really important democratic right. Marching is one good way of advocating for change. But there’s an array of ways that we want students to learn as democratic citizens, which I would say is one of the most important things we can give these kids right now,” notes McDonald.

Adding agency to awareness improves students’ engagement, both in the classroom and out of it.

“They’re learning things in ways that make sense. They can apply them to their lives. They actually see them in application, and it’s joyful,” says Cram.

Just keep learning

In its nearly 50 years of operation, Giddens School has learned a lot about teaching social justice. One of those lessons is that there’s always more to learn.

“I’m always disinclined to say, ‘We’ve got it.’ We don’t have it. We’re working on it. We are very much in a learning process about what it should look like to have these values embedded in our community. Our school is not a place of certainty, but of learning,” says McDonald. That’s a lesson that each of us can take to heart.

|

Sponsored by: |