Editor’s note: Science, technology, robotics, engineering, arts and math: In our schools and communities, there is more demand than ever for STREAM. Yet only about a third of eighth-graders score “proficient” in math and science. In this second installment of ongoing series, sponsored this month by Girl Scouts of Western Washington, we’ll explore how schools and organizations are approaching STREAM in new, game-changing ways.

Editor’s note: Science, technology, robotics, engineering, arts and math: In our schools and communities, there is more demand than ever for STREAM. Yet only about a third of eighth-graders score “proficient” in math and science. In this second installment of ongoing series, sponsored this month by Girl Scouts of Western Washington, we’ll explore how schools and organizations are approaching STREAM in new, game-changing ways.

In the Victorian era, people would celebrate Christmas with side hunts, during which they would shoot and kill birds and other wildlife. But in December 1900, ornithologist Frank Chapman, founder of Bird-Lore (which later became the National Audubon Society magazine Audubon) decided that counting birds was a much better idea than killing them. So he organized a Christmas Bird Census. Twenty-seven birders participated and 25 total bird counts were held that Christmas Day.

Since then, the Audubon Society has continued this tradition each year. Thousands of volunteers young and old hazard the rain, sleet and snow to collect data on bird populations. In 2014, volunteers counted 68 million birds of 2,106 different species. The data, gathered from North America and across the globe, have been used by scientists to evaluate bird populations, migratory routes, species decimation and habitats — and all this thanks to volunteers who are citizen scientists.

What is citizen science?

Before the 17th century, men and women did not specialize in science. They made their livings in other professions. But at that time, there was a handful of men who liked to gather and talk about science each Thursday afternoon at the Bull-Head Tavern in Cheapside, London. Benjamin Franklin was there. Philosopher Robert Boyle, architect Sir Christopher Wren and others were also members. Later to become known as the Royal Society, these meetings became the place where science could be discussed and explored communally by those who were inclined; it was the center of Darwinian debate, and a clearinghouse for cutting-edge ideas and exhibits about the natural world.

Now, citizen science is a way for people like you, me and our kids to contribute to science through volunteerism. Ordinary citizen scientists have applied their efforts to global climate change, endangered species, national weather observations, ornithology, outer space, critter counts, marine life, ant tracking and yes, even the biomes of belly buttons. The miracle is that all the data that these volunteers collect and then share with scientists amount to real scientific change, something that a lone scientist in the lab cannot do.

And today, technology makes collecting and sharing data easier. As a result, citizen science has blossomed. For instance, eBird is an online data collection point for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (CLO). There, citizen scientists contribute the information they collect in their communities, states and even their own backyards. Check out its live data submissions to see how it works.

So why is it important for volunteers to be involved in the science process as citizen scientists?

- Often, large-scale scientific projects require help. For instance, sudden oak death in oak trees is caused by a fungus that has killed millions of California trees. A recent study in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment found that the involvement of trained high school students, teachers and other volunteers over the past six years enabled researchers to learn more about the spread of the disease, and how they could develop predictive risk maps and to give information to arborists making decisions about the disease.

- Science is a field that is dependent on grants and other types of variable funding, which may leave nothing left for extra help. So citizen scientists, as volunteers, help mitigate the financial burden that scientists may bear when collecting and recording data.

- Because scientists can’t be everywhere at once, sometimes volunteers learn things that scientists had never discovered. For instance, in 1997, the class of Diane Petersen, a science teacher at Waterville Elementary School in Washington, documented increased sightings of short-horned lizards, or horny toads, on rural Washington farmland where previously there had been fewer than 100 sightings. Through the now nonoperational University of Washington and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s NatureMapping program, these students compiled their observations and research into a paper that was presented at the Wildlife Society’s 2000 Northwest Section meeting, where their data was accepted by the scientific community.

- Finally, citizen science makes science accessible to everyone. When a school, community or a group of people volunteers for science, it is a reminder that science is a part of our daily lives and that it impacts everything around us.

In a 1957 commentary titled “Science and the Citizen,” Warren Weaver of the Rockefeller Center summed it up best: “No longer is it an intellectual luxury to know a little about this great new tool of the mind called science. It has become a simple and plain necessity that people in general have some understanding of this, one of the greatest of the forces that shape our modern lives. We must know — all of us must know — more about what science is and what it is not.”

Citizen science in our backyard and beyond

In the state of Washington and across the U.S., citizen science is a flourishing force that shapes the minds of our citizens. In Washington, some projects, such as the Pacific Biodiversity Institute’s Harbor Porpoise Monitoring Project or its Western Gray Squirrel Project, are generally open only to adults and college-age students, says Anna Hallingstad, citizen science coordinator for the institute. But plenty of citizen science opportunities exist for individual schools, teen and children volunteers.

In Seattle, citizen science is alive and well at the Seattle Aquarium, where students receive training from experienced field researchers monitoring intertidal areas in central Puget Sound on low-tide days from April through May. Working with approximately 400 high school students from 13 schools, this program gathers data on 24 marine species. That data, in turn, are made available to university, governmental and not-for-profit institutions for the purposes of scientific endeavors. The aquarium’s citizen science program works in partnership with local high school students and teachers, says Nicole Ivey, the program’s coordinator since January 2014.

“It engages students in doing real science and helping us learn new things about the world around us,” says Ivey. “The majority of science experiences for school-aged students include learning about past discoveries from a textbook or engaging in science labs with defined steps and predetermined solutions.” Having this experience to engage in real science, says Ivey, excites students and teachers.

The aquarium also has a Beach Naturalist Program. Students and their teachers go to the beach at low-tide times on school days to investigate what’s on the beach. In 2015, the program hosted 107 schools, says Janice Mathisen, program coordinator. Although the program does not collect data, it is a great opportunity for younger students to experience citizen science.

Also in Seattle, the University of Washington’s Botanic Gardens sponsor the annual BioBlitz, an intense biological survey for which citizen scientists are encouraged to record all the living species, from fungi to mollusks to plants to birds, within a chosen area over a designated time period. Often called a biological census or inventory, the activity is another chance to get the public involved in the biodiversity of a particular area.

Alicia Blood, youth and family education supervisor for the Botanic Gardens, believes that the BioBlitz is a great way for young people to explore the natural world and think like a scientist. “I think that we often look at the natural world around us on a macro level, and opportunities such as our BioBlitz allows you to dig a little deeper and see how much life there is right in front of us,” says Blood.

Families are introduced to the idea on a Friday evening and on Saturday they can participate by taking guided walks to investigate the Washington Park Arboretum. This year’s BioBlitz focused on birds and the ponds at the Botanic Gardens.

The Pacific Education Institute (PEI) in Olympia sponsors FieldSTEM, which is a set of guided investigations, projects and reporting done outdoors. “We have 30 school districts that are planning and implementing a project . . . [with an] environment, agriculture and natural resource focus,” says Margaret Tudor, executive director of PEI.

School districts are also encouraged to customize their own FieldSTEM, says Tudor. For example, in Shelton, Washington, the focus is on Puget Sound, forests and shellfish. Other PEI opportunities for school districts include working with the Washington Invasive Species Council on invasives; the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s photo-point monitoring and habitat data statewide project; and the Columbia River Watershed project The River Mile, which seeks crayfish, plant and animal data from schools in the watershed, Tudor says.

Youth citizen science programs are flourishing across the nation. North Carolina State University’s Students Discover is a collaboration with the Department of Ecology and offers programs on topics that range from an ant tracker to invasive mosquitoes to belly button biodiversity. Free, downloadable lesson plans are available to teachers and provide a classroom map for citizen science, all of which follow the Next Generation Science Standards and Common Core State Standards.

When teachers tell their students that their data is going into a database that scientists are using ... kids think that it’s really cool.

What Students Discover is most interested in is doing citizen science to scale, says Lea Shell, curator of digital media for Students Discover. “We hope to get people interested in science and work with highly motivated science teachers who are interested in communicating the science experience and doing actual science in the classroom.”

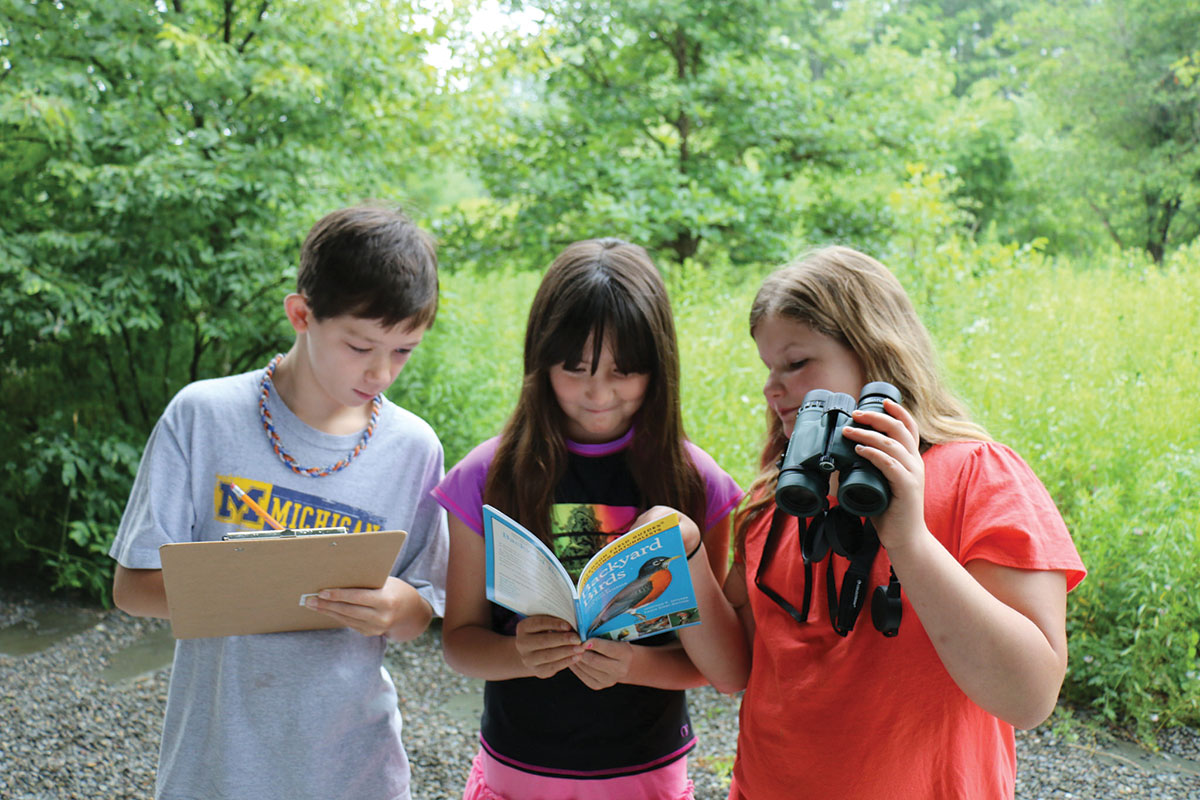

Another opportunity is BirdSleuth. A K–12 inquiry-based citizen science program, BirdSleuth engages students in scientific study, investigation and data collection on bird populations and conservation. Among its programs are Project FeederWatch, the Great Backyard Bird Count, YardMap and NestWatch, all of which contribute data through the CLO’s online eBird database.

Teachers can access free downloads such as the BirdSleuth Explorer’s Guidebook and can lead programs that encourage their students to submit to the annual BirdSleuth Investigator magazine, which features student reports, artwork and poetry. BirdSleuth also offers citizen science lesson-plan kits for educators.

“When teachers tell their students that their data is going into a database that scientists are using to understand [bird] conservation choices, habitat and [species] population protection, kids think that it’s really cool,” says Jennifer Fee, K–12 program manager for BirdSleuth.

Citizen science not only offers an opportunity for all of us to get involved in what’s happening around us, but it’s a reminder that we are important to the process. As Weaver points out, “Our daily lives are surrounded by problems with scientific implications … don’t you think that the time has come when you must give a damn about science?”