Editor's note: This article was sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

It is no secret that Seattle Public Schools, one of the biggest school districts in the United States, has had a spotty track record narrowing disparities — the so-called achievement gap — between its black and white students for decades. As a biracial student progressing on an advanced learning track, local youth Azure Savage discovered firsthand what it is like to try to bridge that educational and cultural divide, and he decided to write about how schools handle race and gender in the classroom.

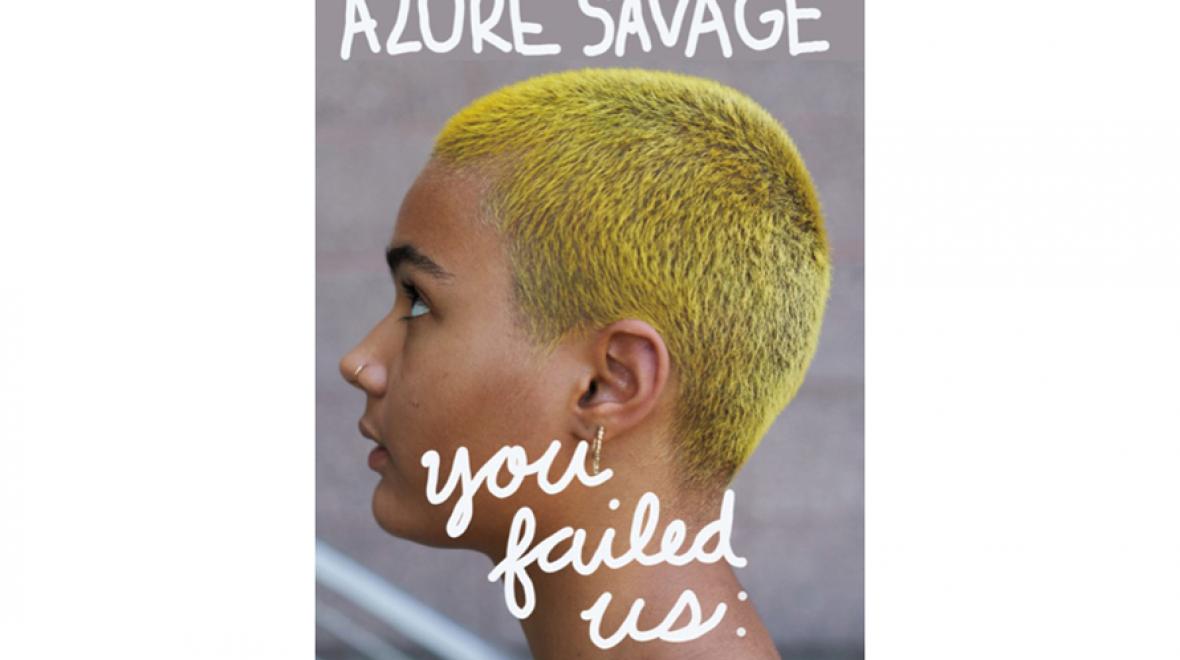

Part memoir, part oral history, “You Failed Us: Students of Color Talk Seattle Schools” candidly explores the experiences of the author and those of 40 other students of color in relation to how Seattle’s K–12 education system and accelerated learning programs, such as the Highly Capable Cohort, continue to hinder equitable achievement for all students.

The 18-year-old author and activist, who identifies as transmasculine, graduates this year from Garfield High School, having completed credits through Running Start at Seattle Central College. We spoke with Savage to learn more about his education journey, the book and what he has planned for after the pandemic.

What motivated you to write “You Failed Us”?

Looking back, I would say it really came from years of my life noticing and being angry at a lot of the inequities that I faced within school being the only black student in my [honors program] class up until essentially eighth grade. I wasn’t able to name what the problem was until I learned more about what racism was, what racism in education was.

I just didn’t really see enough being done about the problem. The book came about because I thought that listening to the students was the most important thing to do, because not enough people listen to students. I started by interviewing peers at my school and then spread out to other schools — that’s how it began.

How has the reception for the book been?

I would say, overall, the reception was positive. I mean, there are people who disagree with what I had to say, but that’s always going to be the case. There are people in the district, specifically from the ethnic studies department and the advanced learning department, who value the work that I did and want to use it to inform their work. That was really cool, to see that my book was able to be a tool in the conversation and in making decisions within the school district.

One of my main goals with my book was that I wanted students of color to feel heard and validated by what I wrote. So, even if no teacher read it or no one from the district cared what I had to say, just the fact that I had a lot of students come to me and say, “Hey, this made me feel like everything that I’ve experienced is valid and matters” — at the end of the day, that’s all that really mattered to me.

How did your personal experience in the honors program impact your identity?

Honestly, I did a really good job assimilating and finding ways to connect to these other kids and even make real friendships there, too. But at the end of it, it was like a performance in a lot of ways. I had to act or hide a lot of how I felt about being in that program, just to feel some sort of acceptance from my peers. And it definitely created a rift between me and other black students, because putting so much work into connecting to white students meant that I didn’t put any work into connecting to black students. So, later in my life, I was regretful in a lot of ways. But as a child, you don’t know that. You’re just trying to grasp onto the acceptance that you can find.

Do you feel that writing the book has given you more comfort and power in your identity?

I definitely feel like my book has made an impact on my life, but I think that for me, coming out and also coming out as trans and then also finding community with students of color, they both came more out of places of real necessity. I just could not live like that anymore. And they both occurred before the book, but I feel like the process of writing the book and getting that all out on paper was very cathartic. It was very difficult, but in a lot of ways, processing it was important.

What do you conclude are the key things that need to change in the administration of our public schools to uproot institutionalized racism?

I have some conflicting ideas around this, because you could say that the reason our schools are institutions of racism is because our society is built off of racism. So, can you really solve the issue of racism within education, in isolation? Or is that something that needs to come with a lot of massive societal changes?

But if we are able to work in isolation, I would say some things that need to change are the processes of discipline and accountability within schools to not be punitive, but rather be restorative. I would say the curriculum of education needs to be more all-encompassing of different students’ stories and histories. Because it’s really disempowering to not be taught about yourself and to be left out of your own education.

Of course, I think the tracking system needs to be dismantled entirely just because creating a hierarchy of students isn’t necessary. It is harmful, not just in the immediate environment of being in school, but creating that hierarchy has long-term effects of who feels more powerful in society overall. Removing any sort of hierarchy of students based off of perceived ability I definitely think is necessary to eliminate some of the inequities.

What would you like to see change with respect to the role students have in informing or shifting policies?

From what I have seen this year, it seems that students are slowly starting to be taken more seriously as people who can weigh in on what should be going on within schools, which I think is a really important step. Especially when you are talking about issues of racism in schools, you need to be centering on the people who are actively experiencing that. And those are the students of color. And it’s a lot easier to just have those voices there to be able to help inform how we move forward, rather than to try to hypothesize, “Maybe this is what they need.”

What’s next for you?

I’m going to be working on my second book, which will be similar to this book, but will cover the nation as a whole from some slightly different angles. And then, whenever the pandemic decides to stop, I’m going to The New School in New York City. I’m going to be attending the Eugene Lang College, which is their liberal arts college. I’m excited about that.