- The towering play structure without grab bars to help a child hoist herself up or a transfer point where she could leave her wheelchair.

- The unbroken railing encircling play equipment, hindering access.

- The sandy surface under a swing set, treacherous to a crutch tip.

These represent the bad old days of playgrounds, prior to implementation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

The ADA, passed by Congress in 1990 and enacted in 1992, guarantees civil rights protection to people with disabilities. Accessibility is one aspect of this protection. For children or caregivers with disabilities, accessible playgrounds are crucial. Accessible playground equipment equalizes outdoor play.

Accessible playgrounds encourage access for all kids -- including those with special needs. They give children of varying abilities the chance to challenge themselves, test and develop their strengths, build large-motor skills and be part of the action. They encourage outdoor play between kids with disabilities and their able-bodied siblings. They also allow parents and grandparents with disabilities to enjoy and supervise their children in a playground environment.

The Center for Children with Special Needs at Children's Hospital and Regional Medical Center publishes a fact sheet summing up ADA guidelines on playgrounds;

ADA Guidelines require that:

- Children in wheelchairs can move around on the playground surface or path to the play area.

- There are transfer ramps with wheel stops and guardrails for children to get onto higher equipment.

- There is separate equipment for all developmental levels.

- The playground equipment and surface are maintained.

- There is space for adults to help children play on the equipment.

- All openings on elevated play platforms are limited in width.

- There are hands-on areas for children sitting in wheelchairs.

Accessible playgrounds may also include quiet spaces for children to rest and regroup from playground stimuli. And the best playgrounds include features that challenge the senses: plants to smell, sculptures to feel, and many textures on which to roll, walk, scoot, drag and crawl over.

All playgrounds for children ages 2 and up that have been built or altered since Jan. 26, 1992, are required to comply with ADA guidelines for playground accessibility. In 2001, the U.S. Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board issued specific guidelines addressing exactly how playgrounds must be accessible.

Playgrounds built since 2001 are therefore generally the most accessible by ADA standards. Existing playgrounds that have not been altered since 1992 are only required to have no barriers to access (such as curbs without curb cuts) and are not otherwise required to comply with ADA.

"As we move toward improving all playgrounds, we work toward meeting all ADA access requirements," says David Jensen, ADA Accessibility Coordinator for Seattle Parks and Recreation. "We contract with people who know what works and what doesn't and involve the community in the planning process." When it comes to improved access in playgrounds, Jensen adds, "even one change can make a difference."

Jerry Nissley, Parks Resource Manager for Bellevue Parks and Recreation, says Bellevue's goal is "making sure our facilities don't exclude anyone. Building accessible playgrounds hasn't been significantly more expensive, and it is paramount to how we serve our customers."

As playground equipment companies respond to the demand for creative play environments that meet ADA criteria, parents can expect to see ever-better accessible play structures sprouting up in parks throughout the region. Playgrounds that meet the 2001 ADA guidelines are numerous and sited throughout the Puget Sound area. Every child is invited to play.

Click Here for a list of local playgrounds built or updated since 2001.

Paula Becker writes ParentMap's bimonthly Park Hopping feature and is a mother of three.

Resources:

- National Center on Physical Activity and Disability Playgrounds For All fact sheet

- Seattle Children's Hospital Playground Safety Sheet

A playground like no other

The Seattle Children's Playgarden, planned for the south end of Colman Playground at 24th Avenue South and South Grand in Seattle, will offer something for every child -- with or without special needs.

Project organizers say the Playgarden will include a unique blend of play features and horticultural therapy. It will be a fully staffed facility where therapists can meet their young clients and work together while digging in the garden, exploring natural environments and enjoying outdoor play equipment.

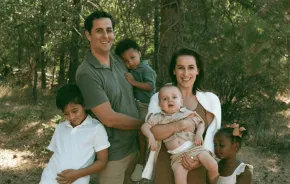

"I've heard many parents talk over the years about how hard it is to find places where all of their family members can play safely and have fun together outdoors," says Liz Bullard, founder and guiding light of the Playgarden and a speech and language pathologist at the Boyer Children's Clinic in Seattle. The Seattle Children's Playgarden, Bullard says, will answer this need.

While the Playgarden is designed for "any child with a condition that somehow influences the way they can access outdoor play," Bullard adds, it will be welcoming for all children. "This is not just for kids with special needs."

Plans for the ambitious project include edible, sensory and alpine gardens; an accessible tree house; streams; cave, marsh and meadow environments; climbing mounds; a sandbox; play features that encourage gross motor skill development; and a building for offices and community use. A fully wheelchair-accessible basketball court, funded by the Seattle Sonics/Storm Foundation, is currently under construction. The Seattle Parks Department owns the park but the Playgarden project will finance the building of the structures, sign a long-term lease and pay for staffing and maintenance.

Unlike most local playgrounds, the entire perimeter of the Playgarden will be fenced. "We want to give the kids as much freedom as possible within the space," Bullard explains, "and many parents of kids with special needs say that they simply can't take their eyes off their children for a minute. Little kids with Down syndrome who like to run, for example, or certain kids with autism who don't stop when their names are called. Some kids are also really afraid of the outdoors. The boundary fence will ultimately support autonomy in the kids."

"The Playgarden project, as currently envisioned, has no equivalent in the Seattle metropolitan area," says Pam Klimnet, project manager for the Seattle Parks and Recreation Department. In fact, Liz Bullard's research has turned up only two similar projects nationwide.

The Seattle Children's Playgarden is currently raising money to support the park's development. "We are actively seeking more board members, and I am excited about talking to parents of more school-aged kids with special needs," Bullard says.

For more information, check out the Seattle Children's PlayGarden website.