It started with a simple game of Memory at a recent family game night. We were all enjoying ourselves, right up to the moment when my 8-year-old went on a matching streak that caused my 5-year-old to spiral into a full-on tantrum. I watched this brewing, secretly hoping the little guy would get a match on his next turn.  Short of purposely letting him win, we tried our best to help our preschooler stay in the game — and then deal with the emotions that come with losing.

Short of purposely letting him win, we tried our best to help our preschooler stay in the game — and then deal with the emotions that come with losing.

Unfortunately, this has been my 5-year-old’s experience with most board or card games for the past year. Which makes me wonder: Should I just let him win?

I’m not the first parent to ponder this dilemma. Many are split on the issue. One mom, posting recently on Parentdish.com, walks the line — by opting out: “I would not let a child win constantly, but I would also not play a game of skill against a child who stood a high chance of losing.” I realize that’s exactly what my family is doing when we’re pitting our adult and 8-year-old’s skills against a 5-year-old’s. He’s bound to lose every time.

A good loser?

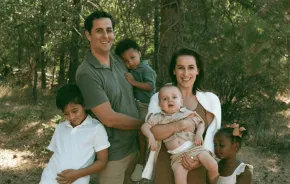

Some say losing is good — because it teaches kids how to be “good losers.” “I would never let my kids win,” says Monica Alverez, a Kenmore mother of three girls. “They need to learn that there is going to be a winner and there is going to be a loser, and when they’re the loser I want them to have good sportsmanship, because you need to learn that in life.” Alverez says that when her children do win, they are proud of themselves, because they know they really earned it.

Benny Colobong, an Everett father of two, doesn’t take a hard line against throwing a game or two; he occasionally lets his 4-year-old daughter win. “My wife and I believe it is our job to prepare our children for how to deal with the world without us. In life, you’re not always going to get everything you want; you’re not always going to win.” He tries to strike a good balance of sometimes letting her win, which gives her encouragement to stay in the game. “I let my daughter win once in a while because then when she loses, she knows it’s not that bad — she can always try again next time.”

Many parents say that letting a young child win can boost self-confidence, not to mention alleviate frustration when a well-intended family game night disintegrates into a battle. Monica Wheaton, a Lynnwood mother of two boys, ages 2 and 4, says she doesn’t think letting little kids win is a bad thing. “You have to let your kid have some successes, and it really helps their confidence,” she says, not to mention giving them a chance to practice winning gracefully.

Still, sometimes Wheaton’s family tosses the rules and just plays creatively. “Sometimes my husband and I just play along with them, not necessarily going by the rules of the game, and that doesn’t make it such a big competition. It’s not just about winning or losing. They get to learn counting, and letters, and colors and just have fun making up their own game.”

Change the focus

Taking the emphasis off winning and losing — like Wheaton’s family sometimes does — makes sense for very young children, according to Judy Burr-Chellin, director of parent and child services at Wellspring Family Services. Preschoolers don’t yet have the mental ability to understand the concepts of winning and losing — or even the rules of structured games, for that matter. “At 3 to 5 years old, children are only just beginning to understand group play, so the idea of a board game is really hard,” Burr-Chellin says, and tears and tantrums are one likely result. If the emphasis is taken off of rules and winning, and put instead on spending time together (and very loose interpretation of the rules), kids gain, according to Burr-Chellin. “The most beneficial thing about games with young children is the positive interaction they get with adults. When they notice an adult is paying attention to the things going on in their mind, it shows them those things are important.” This helps a child to learn to see her own thoughts and ideas as important as well, says Burr-Chellin, which is an essential reflective process that develops in the preschool years known as “mentalizing.”

Instead of games that focus on competition and skill, Burr-Chellin suggests those that involve fantasy, imagination, playfulness and storytelling. She recommends dress-up, using toys like stuffed animals or puppets to tell a story, blocks, Legos and drawing. She also suggests cooperative games, in which the goal is not about winning or losing and everyone works together. The one traditional board game she does like for this age is Candyland, because it’s not a game of skill. The game takes place in a pretend world where preschoolers can enjoy colors, candies and fun characters … and the very real chance that they’ll actually win, fair and square.

Katie Amodei is a Lynnwood-based freelance reporter and mother of two.