Photo:

Photo credit, The Little School

Editor’s note: This article was sponsored by The Little School.

Traditional schooling methods — long hours sitting still indoors, rote memorization, high stakes testing — seem designed to crush children’s curiosity and natural love of learning. But school doesn’t have to be like that.

“The inner drive to learn is strong in humans, and we want to attend to that,” says Regan Wensnahan, director of enrollment management at The Little School, an independent early learning through fifth-grade school in Bellevue, where authentic learning is driven by students’ natural curiosity. Instead of making school something to dread, “Children should think of learning as something that doesn’t just happen in the classroom, but as part of life.”

Authentic learning

The Little School’s philosophy of authentic learning is an outgrowth of the progressive education philosophy first espoused by education reformer John Dewey and informed by the newest brain research.

“Authentic learning is centered around this idea that learning shouldn’t be abstract to a child. It should be relevant and engaging. It can either be responsive to something that the child is thinking about, or it can be expanding beyond their experience into something totally new. But it’s engaging at their level and drawing them further in,” explains Wensnahan. “Whether they’re studying a caterpillar they found or the Arctic, where none of the students have ever been, the focus is on developing a complex understanding of the subject.”

To make something unfamiliar — like the Arctic — relevant to students, lessons must include points of reference to their own lives. They may talk about what the students wear when it’s cold and compare that to the clothing of the Indigenous people of the far North. Resources like Burke Boxes help make concepts more concrete for learners.

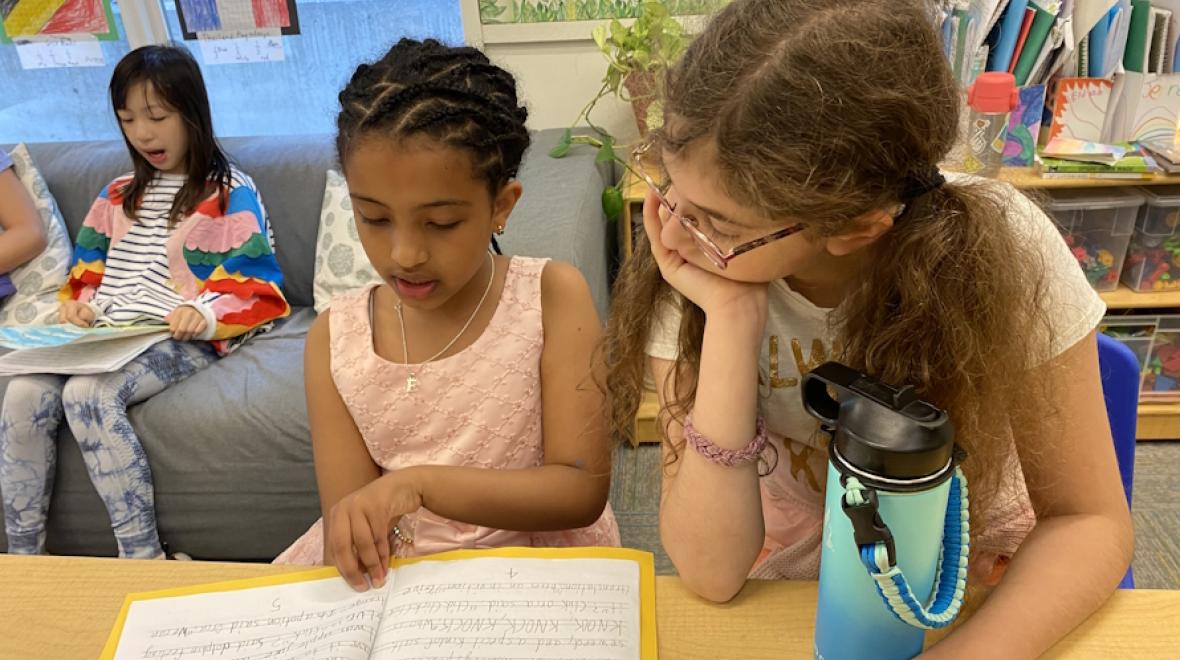

“Learning in community with peers is another element of authentic learning,” adds Braden Wild, advancement and data manager at The Little School. “Authentic learning is grounded in place and in the context of the learning environment.”

The Little School campus is a 12.5-acre woodland that serves as an extension of the classroom. Students’ own observations of their environment can launch learning experiences. The discovery of a caterpillar on the trail can lead to species identification or a discussion of metamorphosis or the food and habitat needs of caterpillars.

Hands-on, project-based learning is not just reading a textbook and answering questions. Authentic learning seeks to incorporate as many modalities as possible. So, a second-grade Farm to Market unit could include a field trip to Pike Place Market to interview vendors and purchase ingredients to cook back at school.

Curiosity-driven learning

Curiosity is a state of mind that can be nurtured and even taught. Curiosity-driven learning follows consistent steps.

“Curiosity starts with paying attention. We help our kids notice what’s going on around them, pay good attention both to the place where they are and the people that are around them or the ideas that are being talked about,” says Wensnahan. Next, you think about what you already know in order to take the third step, identifying what you don’t know and what questions you want to answer. The fourth step is figuring out how to find the answers.

The Little School students learn that there’s not just one way to learn. Reading is one way, but so is building a model or drawing a picture or conducting an experiment or an interview. Last year, after fifth graders learned about brain anatomy together, they formed small groups that designed their own brain research projects for more independent learning.

Whether it’s choosing ingredients or research topics, “Implicit in all of this is choice — if something is tickling your brain, that’s a great place to start learning more. Within a bigger topic, there’s often opportunities for kids to make choices about where they start or what part of it they focus more on,” says Wensnahan.

People often overlook the final step, which is the most important one. The old saying is true — the best way to learn something is to teach it. At The Little School, students solidify their learning through some kind of model or presentation, giving kids the chance to share their thinking with others.

Museums of Learning

At The Little School, these age-appropriate presentations are called Museums of Learning. They can be traditional presentations or resemble a classic science fair with posters, models and demonstrations of experiments. One group whose brain research studied the role of story in memory formation gave a puppet show and then tested the audience’s memory of the story.

Museums of Learning are not limited to scientific topics, and no child is too young to participate. Last year, one early learning class became fascinated by airplanes. They set up a play space with headphones for a pilot, trays for flight attendants and chairs for passengers. Then they invited another classroom to play airplane, taking turns at all the roles. Kindergarten classes might teach a dance to another classroom or complete a group project to share with their families — an ideal audience.

By fifth grade, students are ready to take on an independent capstone project where they choose their own questions, conduct their own research and develop a presentation to share with the whole school community. Part of the assignment is to ensure that their presentation includes activities that can work for small children as well as adults.

Authentic learning at home

Even if your child’s own classroom skews towards rote learning, you can help keep their curiosity alive.

The first thing is helping children connect what they’re learning in school with their daily life. It’s also important to lead by example. Parents who are used to having (or pretending to have) all the answers might struggle to model curiosity. Don’t just quiz your child. Instead, use phrases like “I wonder” and “That makes me think about …”.

Crafting good questions is part of what allows you to think more critically. Whatever bridges you from a factual answer to a deeper thinking answer is good. When you’re teaching kids how to ask good questions, start with the basics — who, what, when, where, why and how. But don’t stop there. Ask a powerful follow-up question: So what?

“Part of the intellectual journey is learning how to frame a question to get the information you really want,” says Wild. Now more than ever, media literacy — learning how to recognize whether an answer is good or bad — is also important.

“I think we are ruled by Google too much. Just because Google puts it up first doesn’t mean it’s your best source,” says Wensnahan. Instead of blindly relying on search results, try starting with the library. Besides loaning books, library websites link to reliable online resources. Links and information on the websites of universities and other known educational organizations are other quality sources.

Be a family that asks questions. Authentic learning can take place wherever you let curiosity lead you.

|

Sponsored by: |

|

|