Are you the kind of parent that says, “Hey, turn that frown upside down!”? Or the kind that thinks that it’s a shame that the story of Bambi starts with a dead mom, the Grimm Fairy Tales are too grim or the children’s authors Maurice Sendak and Roald Dahl focus so much on the dark side of life?

If so, you may not like the new Pixar film, Inside Out, which takes you and your child on a tour of negative emotions. Family bonding, happy times and good forces prevail as the heart and soul of the film — but the film’s message is that negative feelings, especially sadness, have valid roles in life as well.

A quick background: As you probably know by now, the film’s hero is Riley, an 11-year-old girl whose family moves from Minnesota to San Francisco. Riley’s emotions are characters, and most of the story takes place in her head. Initially, Joy directs the life of Riley like a dominating CEO. But with the jolting experience of their move and her coinciding, developmental transition to pre-pubescence, other emotions jockey for center stage – specifically Fear, Anger, Disgust and Sadness. They grab at the “joy-stick” of the control panel in Riley’s brain with the ferocity of experienced gamers.

The neuroscience of emotions

The competition between Riley’s emotions illustrates what actually takes place for most kids during the tween years and eventually their teen and adult years. This film gets the developmental psychology and the neuroscience of emotions right, which should be no surprise since the movie makers consulted with the gurus of emotion research, Paul Ekman and Dacher Keltner. Parents and kids alike will learn about emotions, core memories, and the fact that we are only conscious of a shred of what goes on in the emotional (limbic) centers of our deep brains.

Riley has been socialized by her parents to keep Joy as the emotion who runs the show, with quips like, “Where’s our happy girl?” if she looks sad, and monkey noises to keep the laughs coming. Riley’s parents are decent folk and represent society’s value on positivity. Don’t we all want our kids to be happy or try to be happy?

As for all of us, Riley’s life experiences naturally trigger Fear, Anger, Disgust, and Sadness. Animations show that these players in her interior life are as important as Joy in influencing how Riley reacts to things and how she feels, thinks and acts. And importantly, they help her interpret human experiences and enrich her understanding of others.

Emotions are associated with behaviors and facial expressions, but they are abstract as concepts. Since animation can make feelings “real” and concrete as characters, this film is a walking, talking endorsement and even aid for social and emotional learning. Young viewers can “see” emotions as characters and appreciate them. Hopefully parents can too.

Young children are fairly concrete in their understanding of events and limited in their ability to identify feelings related to them. Abstract concepts like emotions are a stretch for children. Nevertheless, our goal as parents is to help children enhance their emotional intelligence, which allows one to identify emotions, understand the cause of them, control them, read them accurately in others, develop empathy, and use emotional awareness to inform wise decision-making and problem-solving.

Even toddlers can begin identifying feelings like “mad,” “sad,” and “scared” when we insist they go to bed, scold them for hitting their sibling or nudge them toward an unwelcome, new activity. The film provides parents with assistance for this venture because they can discuss feelings as entities within all of us and validate them.

I attended the film with a 26-year-old teacher of sixth graders, who had previously taught 1st graders in the Teach for America program, all of whom were living in impoverished homes of one kind or another. By the time we had driven home, she had already devised post-viewing lesson plans for children of different ages and circumstances.

As a psychologist, I became eager to talk about the film with the kids I see in my practice. As a parent, I enjoyed talking about it with my daughter. As a daughter, I enjoyed talking to my mom about how vulnerable I felt when our family moved from New York City to Houston when I was 11 years old. Yes, I too experienced sadness, like Riley, as well as fear, and I perceived disgust from my peers because I was a nerd. Emotions can drive us apart or together, but talking about this film can be a bridge for parents and kids alike.

Diving into negative emotions with your kids

Negative emotions are omnipresent. However, we avoid talking about them, and then our kids pick up on that bias. You can talk about your own experiences and be a model, not just “interview” your kids! Ask questions like:

- What is a memory of sadness you’ve had, and how did you express your need for understanding and support?

- Has anger helped others respond to your needs?

- When did you have an experience like Riley’s when she blew up at the hockey try-out, and anger led to a misunderstanding?

- When did disgust or fear protect you? How does sadness help you feel for others when they get hurt?

Tweens and teens will identify with many of Riley’s plights. The film may stimulate good conversations and emotional connections for parents with their tweens. But since emotional awareness is the whole point, don’t blow it with unwanted intrusiveness. Their cues should guide you.

For kids ages 7 and younger, it might be fun to have kids draw their own characters for different emotions. When kids seem moody, they can present one of their drawings which may jumpstart a connection about a difficulty.

I’m on a mission to enhance emotional intelligence. My new book for parents of 3- to 7- year olds (Getting to Calm: The Early Years) is largely about dealing with both parents’ and children’s emotions, especially when they collide. Whether the challenge is tantrums, cooperation with chores, or sibling quarrels, emotions are driving the maelstrom. Little kiddos need help with identifying their negative emotions. And almost all parents need encouragement to validate their children’s negative feelings and perceive them as opportunities for understanding what’s going on within their child and how they can help them.

Too often parents are busy, find negative emotions aversive or messy, and become judgmental about their children’s perfectly natural reactions to life events. Sure — discipline comes into the equation too, but often parents rush to that agenda without taking the time to enhance their child’s emotional intelligence. We don’t want to send a message that we want to get rid of negative emotions, but our own negative reactions trump connection on a regular basis.

The amygdala hijack

One of my favorite scenes is a showdown that Riley has with her parents about her bad attitude at their dinner table. We get to watch the parents’ control stations go haywire as their Anger, Fear, and Disgust create havoc within their brains, then with each other’s, and then with Riley’s.

The dinner table blow-up is an ideal depiction of what brain scientists call an “amygdala hijack.” The amygdala, AKA Fear, is in charge of responding to danger. It strikes an alarm that tells our bodies we are in a life-threatening situation. Sometimes the Fear sentinel is accurate, like when the skillet catches on fire. But a lot of the time in modern life, Fear gets triggered by stressors like traffic, people that disagree with us or children who are acting like children (like Riley at dinner, who doesn’t know how to express her negative feelings about her many difficulties with the move).

Signals traveling this network take over and we can’t access our rational brain circuits temporarily. Whenever you lose your temper or react to your darling tyke in a way that you regret, your control panel (e.g. your prefrontal cortex) is probably jammed up with emotions and conflicting directives, just as you see in the brains of Riley’s family at the dinner table. What a mess. We all experience these cluster bombs of emotions in our families, but now we have an animated form of a neuroscience lesson for understanding them.

You can’t watch this film and not develop more empathy for the landscape of children’s emotions. Loss, humiliation and rejection are inevitable and neural pathways of sad thought processes and memories are established just like the ones illustrated in the film. Will your children feel nurtured through these experiences and remember human attachments as rewarding and meaningful? Or will they feel abandoned and neglected because their negative emotions are rejected, dismissed or overlooked?

While much of the material will be over the heads of young viewers, they will enjoy the antics of the competing emotions. Like other Pixar films, the spectacular visuals and basic story line entertain the young viewer while the teens and parents enjoy the puns, metaphors and allusions.

Ticket sales will tell us whether Inside Out is as successful in entertaining parents and kids as the other Pixar films (I think maybe not), but how many will be discussed by teachers and psychologists as aids for social and emotional learning?

The film’s take-home message is that negative emotions have a function. They are important. When accurate, they protect us and maybe even save our lives. Sadness acknowledges the pain of loss. Moreover, Sadness helps kids develop empathy for others who experience loss. Empathy builds a bridge for compassion, connection and intimacy. And a little stepping stone for supporting this awakening ability is this little Pixie of a film.

Four more movies that teach emotional intelligence

Four more movies that teach emotional intelligence

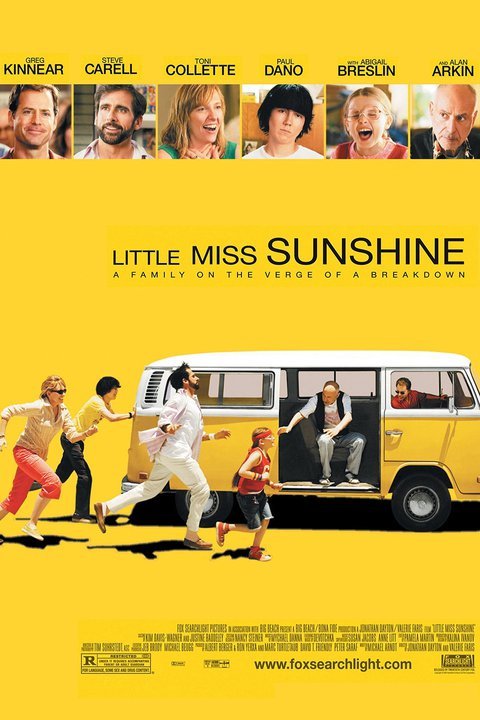

Little Miss Sunshine: For teens and tweens, this movie about a “dysfunctional” family shows the best way to handle a teen’s “amygdala hijack” I have ever seen, where the boy learns that his color blindness eliminates him from being able to become a pilot when he grows up. He screams bloody murder and hateful epithets and bursts out of the van to sit on the hill. The parents do not talk, murmur some empathy but remain quiet. After a while, the boy’s sister puts her arm around him. They resume the trip without talking about it, giving him the space he needs for now to recover.

Whale Rider: A film about a Maori girl that deals with assertiveness, Girl empowerment, cultural awareness and family loyalty. For teens and tweens.

Amelie: The magical French movie a young Parisian on a mission to spread optimism, kindness and empathy. Also for teens and tweens.

Happy Feet: The film about a misfit penguin helps kids learn about accepting others that are different or vulnerable, the Golden Rule and the importance of taking care of the environment. For younger kids ages 5 and older.