When it comes to raising a teen, Raina Johnson of Auburn calls herself “blessed.” Her 17-year-old son is thoughtful and responsible, conscientious about school and kind to his two younger brothers. Throughout elementary school, his sleep schedule was equally dreamy: in bed by 7:30 p.m. and up around 6 a.m., rested and ready for the day.

But when her son was in middle school, Johnson noticed a change. By age 12 or so, Aidan started taking longer to nod off at night and had more trouble waking up. That’s continued as he’s grown. These days, the kid who used to hit dreamland before 8 p.m. is now a night owl who sets two morning alarms to make sure he doesn’t miss the bus, and sometimes crashes by 3 or 4 p.m. — just when he needs to start homework.

Helping teens get more sleep: tips from ‘The Sleep Doctor’

- Set a schedule for the week. A good sleep routine includes a regular bedtime that’s based on a realistic waking time. If your teens need to be up at 7 a.m. during the week, then a 10 p.m. bedtime will allow them the approximate nine hours they need.

- Set limits on technology. The bedroom should be free of technology. Set an electronic curfew for your teenagers that allows them to wind down for an hour or so before bedtime.

- Get outside and get moving. Exposure to sunlight — especially in the morning — strengthens circadian rhythms, helping us to feel less tired early in the day and readier for bed at night. Exercise, too, will help to keep teens’ body clocks in line with their bedtimes and waking times.

- Talk to your teenager. When you’re setting bedtime schedules and limits, discuss why these things are important. The more your teens understand about their bodies’ changing needs for sleep, the more they can actively participate in learning to manage their own sleep habits.

— Malia Jacobson and Michael Breus, Ph.D., “The Sleep Doctor”

As any parent of a teen knows, this isn’t a unique problem. Today’s teens are chronically tired, says Dr. Maida Chen, director of Seattle Children’s Pediatric Sleep Disorders Clinic. Although teens need between 9 to 10 hours of sleep, most skimp; per the National Sleep Foundation, just 15 percent of teens get enough sleep at night.

The result: moodiness, distracted driving and difficulties waking up — a struggle that’s especially painful as teens readjust to an early alarm clock during the first weeks of the new school year after a summer of sleeping late.

“Sleep deprivation impairs [our teens’] academic ability, their cognitive performance, their ability to interact with peers, their emotional maturity and their already impaired adolescent judgement,” Chen says. In other words, chronic sleep shortage can make the topsy-turvy teen years even more turbulent.

Body clock, behave

Teens who stay up late and morph into zombies come morning aren’t being defiant, and they aren’t unusual, says Chen. Their behavior is biologically driven, and can be seen in a number of animal species. Around the time of puberty (typically between ages 11 and 14), circadian rhythms shift to favor later bedtimes than those in early childhood.

“Often, a teen won’t go to sleep before 11, no matter what you do,” says Chen.

So, a teen who needs to wake by 6 a.m. will start each day a couple of hours short on sleep, struggle through the day and then repeat the cycle. It’s not hard to see why hitting the snooze bar might become a habit, says Dr. Darius Zoroufy, a somnologist at Swedish Medical Center.

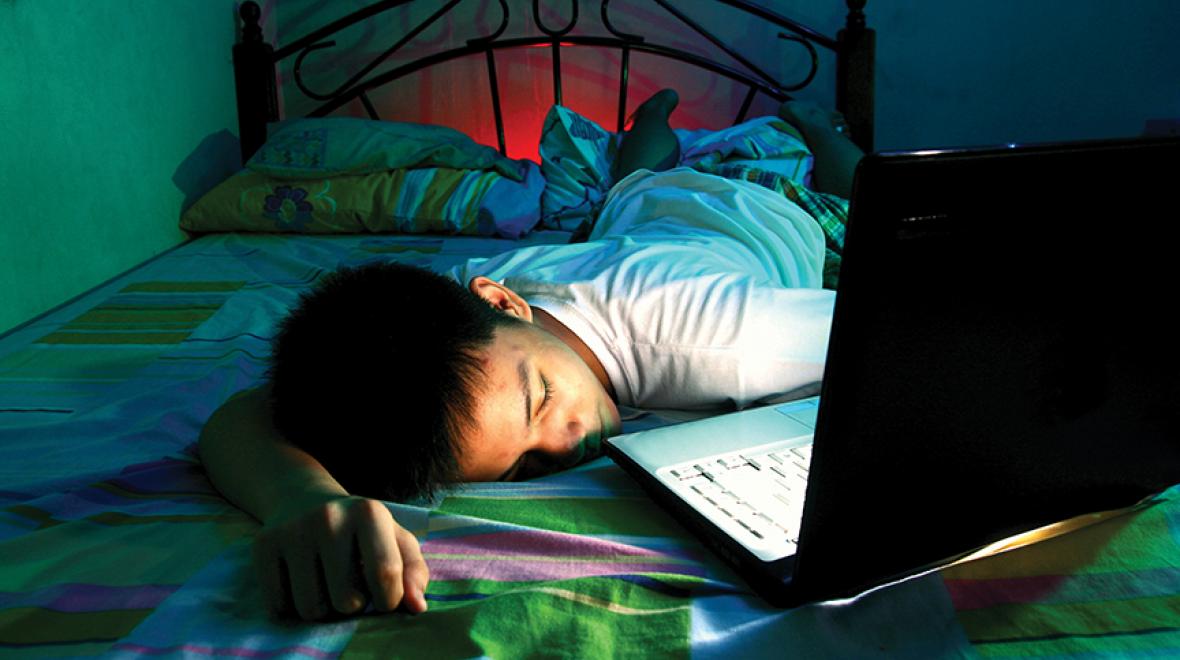

The late-to-bed, later-to-rise behavior also has a social basis, says Zoroufy. As social activity moves online for teens, many have near around-the-clock access to friends. A budding, buzzing social life is normal and healthy, he says, but it can also rob teens of sleep. “When the night hours become a time to connect to peers online, sleep isn’t as much of a priority,” he says.

Saved by the bell

Seattle’s school starting times have already shifted to better match teens’ biological rhythms. In 2015, Seattle Public Schools became one of the nation’s largest districts to move opening bells for school to 8:30 a.m. A new tiered bell schedule for 2017–2018 starts the school day at high schools near 9 a.m.

The move to later start times, recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics and championed by Chen and others, reflects an increased understanding of teens’ unique biological patterns that favor sleeping later in the morning.

“In the past, expectations of when a teen should be up and functional in the morning just didn’t align with their biology,” says Chen. Later school times are backed by science and good sense, she says. When teens are allowed to wake at 7 a.m. — or later — and can still make it to school in time, they have a better chance of staying rested.

Healthy habits

Of course, even a later alarm clock might not help teens who routinely struggle to get up. For some, a daily sleep schedule that’s inconsistent leads to a sort of permanent jet lag. Teens who spend the week sleepy often “binge sleep” on weekends, says Chen. This makes it difficult for them to fall asleep on time, perpetuating a negative cycle.

Helping teens wake earlier and more easily — or adjust to a back-to-school sleep routine — means focusing on when they awake, which sets their body clock for the rest of the day, says Chen. “This means making sure teens consistently get up at the same time within an hour, each day, including weekends.”

Caregivers shouldn’t be afraid to set limits for teens, says clinical psychologist Michael Breus, Ph.D., an expert in sleep disorders who is also a parent of two teens. Although teens may chafe at “bedtimes,” they still need and respond well to routines, especially ones they help create. >>

Asking teens to think about how much sleep they need to feel rested is a good start. A teen with a 6 a.m. wake-up call needs to be in bed by 10 p.m. to get eight hours (a reasonable goal, if short of the recommend 9–10 hours). To set a bedtime, work backward: Homework needs to be finished by approximately 8, and personal electronics need to be switched off by 9.

That’s right: Electronics need a bedtime, too, says Zoroufy. Per a November 2016 study in the scientific journal PLOS One, light and stimulation pouring from teens’ smartphones can keep them awake by curbing the production of the sleep-inducing neurotransmitter melatonin. So, set a “power-down hour,” or a time to retire all gadgets to a charging station, outside the bedroom.

Adults, this means surrendering your devices, too. Modeling healthy habits is key here, says Zoroufy, and — bonus! — your own sleep habits will benefit, too.

Dream onGet more top sleep advice from author Malia Jacobson in her new monthly column. |