We all know a family that’s done it — packed their bags, pulled up stakes, pressed “pause” on regular life and . . . left. Perhaps for Ecuador. France. Thailand. Maybe bringing jobs with them, maybe volunteering, maybe dedicating the time wholly to cultural exploration and family bonding. More than a vacation, less than a permanent move — let’s borrow the language of the pre-college adventurer and call it the “family gap year.”

Families that have taken a gap year (or two years, or six months) get used to a standard reaction:

“Man, I’d love to do something like that.” But that first, wistful sentence is almost always followed by a litany of what makes the adventure too hard: houses, jobs, money, school, social commitments. Life. How can we just leave?

It’s daunting, to be sure. But every year, a subset of determined families turn the “too hard” idea on its head and set out — and off — to change their lives.

My family of five was among them; we spent a year in Costa Rica a decade ago, and it changed us forever.

For this story, I sought out other families who also left the U.S. on a leap-of-a-lifetime to explore the common threads of our experiences: What was harder (or easier) than expected? What was the impact on families two, five, even 10 years out? And the biggie: Did the time-out give us — especially kids — the kind of perspective on our complicated First World culture that many parents long for?

Too hard? As it turns out, for many parents and their kids, a gap year proved to be the quickest path to the stuff — values, family time, real-life experience — that matters most.

All that packing and planning? Those are just logistics.

Independence days

At that age, would we have sent her [on her own] to run errands? No, we wouldn’t have done that.

Many families who take a gap year want their kids to see the world as a place of thrilling potential, a wonderland to be explored. In other countries, kids are given more freedom and autonomy at a younger age than here in the hovermom culture in which many of us live. Such cultural support for kid independence makes it easier for parents to loosen the reins.

Sherry Smith and Matt Huston of Seattle moved to Cajamarca, Peru, for six months when their children, Sam and Sally, were 14 and 10. They immersed themselves in Peruvian culture — the kids were the only non-Peruvians at their school — and the parents found themselves letting Sam and Sally do things by themselves “that we’d be reluctant to let them do here,” says Huston, a middle-school teacher who was able to take a sabbatical.

In Cajamarca, Sam would ride a moto to explore the next town over, or take a couple of buses to a soccer game. “Or I could say, ‘Sally, could you run out and get some powdered sugar?’” Smith says, an exhibit writer. “And she’d come back 35 minutes later, and I’d be fine.” Adds Huston, “At that age, would we have sent her into Ballard to run errands? No, we wouldn’t have done that.”

Passport to problem-solving

Hand in hand with independence come the ownership and creativity required for solving problems. We all want to raise kids who are problem solvers — but first, something has to go wrong. Travel has a way of flinging glitches in our paths. Family after family talked about their kids’ ability to rise to — and resolve — the unexpected.

Three years ago, Dianne Fruit, a Spanish instructor, spent six months traveling and volunteering in Central America, South America and Europe with her family: Chris Eastland, an engineer, and sons Ridley and Rory. “Our kids got this great ability to roll with the punches,” says Fruit.

“I don’t get as frantic now when something goes wrong,” says Ridley, who was 13 during the trip. “Instead, I just think ‘OK, what can I make happen?’ Back home, every day could be an adventure, but the likelihood that something unique is going to happen is just a lot less.”

We parents can handle (or prevent) much of the trouble that crops up on our home turf. Outside it, the kids get to step up in ways we’d never have dreamed.

During my own family’s year in Costa Rica, our kids — ages 5, 9 and 12 at the time — had myriad opportunities to problem-solve, most notably during a weeklong trip to Panama.

In Seattle she was still a little girl; at the border, she talked us into Panama and out of disaster.

We’d spent 12 hours on an assortment of steaming buses to get to the Panamanian border, only to be denied entry for reasons I wasn’t able to understand. The bus was long gone, we were exhausted — and our side of the border offered no services and nowhere to sleep. I was used to being the grown-up, but my Spanish was not up to this task.

As I choked back tears, our eldest daughter stepped up to the counter. Twelve-year-old Hannah spoke to the immigration official with a fluency that dropped my jaw. In Seattle she was still a little girl; at the border, she talked us into Panama and out of disaster.

Traveling far to be close

There’s nothing like facing the same problems at the same time, whether they’re tiny glitches or near calamities, to bring members closer. A gap year makes the whole family strangers in a strange land together. Many families report newfound closeness between their kids as one of the most lasting and tangible effects of their time away.

Ashley Steel and Bill Richards, professional ecologists from Bellevue, Wash., moved to Vienna for six months when their daughters, Zoey and Logan, were 8 and 5. As they traveled through Europe, they “built a little lexicon of misunderstood words and private jokes that has lasted more than six years since we returned,” says Steel. She cites the time she confused the German word for “chaos” with “cows” in a conversation with an Austrian administrator. “Now whenever a situation dissolves into a chaotic mess, someone in our family will cry out, ‘It’s all cows!’”

“Definitely the two of us are closer,” says Zoey of herself and younger sister Logan. “Now that we’re back, we have our separate friends and lives, like before, but . . . there’s definitely something about having only had each other for all that time.”

Fruit says of her family’s year away: “Our family is even more unified now. We learned more about one another and have a shared narrative that is common to just the four of us.”

Opening kids’ eyes to #privilege

And of course, the big question: What happens to us, to our kids, when we get perspective on an issue so large it has its own hashtag: #FirstWorldProblems?

“One of the most lasting effects of our travel is our kids’ increased awareness of the difference between needs and wants,” says Chris Eastland, Fruit’s husband. A gap year can be anywhere, but families that traveled in the developing world report that everyone’s sense of what’s required was recalibrated: Smartphone? Want. Food and clean water? Need.

Parents want to help their children understand that they don’t live on the “have-nots” end of the socioeconomic spectrum, and most of us have a really good lecture about that. Mine used to begin, “You have no idea how lucky we are . . . ,” and I pulled it out whenever my kids even hinted at a complaint about sharing a bedroom or not having an Xbox.

Surprisingly, this lecture never made my children feel particularly lucky.

But our family had to think, hard, about the meaning and responsibility of our own privilege when a pair of Nicaraguan children stood silently, 3 feet from our lunch table, hoping we might leave something on our plates when we left.

As parents living in one of the richest regions of one of the richest nations on the planet, raising kids who truly understand the truth and responsibility of their privilege is hard. But when we see, live and feel the situation of so many who share our world, we live the lesson.

And we learn, tritely but truly, that less really can be more. “I loved the people so much,” says Huston of his family’s community in Cajamarca. “We would go to the mercado, and everyone was friendly, and they knew me. Here, you go to the grocery store, and there probably won’t even be a checker anymore — just a machine.”

It’s also important to note: Far-flung lands do not exist for the edification of traveling families. In taking ourselves to other countries and cultures, both visitors and citizens have the opportunity to edify each other. The question is not just, “What can this kind of travel do for my family?” but, “What can my family do for the world, by being in it more?”

Of course, a year in Paris is less likely to highlight the inequality of privilege than a year in Peru. But whether it’s economic privilege or cultural consciousness, living elsewhere teaches our kids that the way we do things at home is not the only way.

It’s not all rosy

And what about the downsides? Or is the family gap year just months on end of rosy togetherness?

Everyone agrees: Extended travel has its challenges.

For one thing, when you move to a different culture, you get a different culture. The Kardashians notwithstanding, the USA does not have a lock on cultural bummers. Just ask Sally and Sam. The local Peruvian culture had a harsh surprise for athletic Sally, who attended fifth grade in a town where only the boys played organized sports — girls sat on the sidelines, watching.

And Sam found that it wasn’t just the Spanish that made the math completely foreign.

“We knew school would be all in Spanish, but we didn’t think how different the rest would be,” Sam recalls. In addition to the lack of sports at recess, “The kids all spent the day in one room and didn’t move around,” says Huston, Sam’s dad.

Unmoored abroad, couples can also find themselves disconnected, especially when one parent is working while the other isn’t. Sharon Chen and Peter Carlin moved their family to Taiwan when Carlin, a software developer, convinced his company to relocate him for two years. With kids ages 5 and 3, Chen, a stay-at-home mom, was suddenly functioning without the support network she’d built at home. “Peter traveled for work a lot,” she says, “and that part was really hard.”

Missing school in the states can pose academic challenges, too. Lucy Carlin was 5 when her family left. In Taiwan, she learned how to read and write in Chinese — but not in English.

“Coming back, Lucy was significantly behind her age group in reading,” says Chen. “For probably two years that was something we had to manage with teachers.”

And social lives can suffer. Returning from our family’s gap year, our newly bilingual oldest daughter, Hannah, whose peers couldn’t fathom how she had spent seventh grade, spent eighth grade lonely and isolated.

But downsides can lead to upsides. Hannah says of all that pain, “I pay a lot more attention now to people who are on the outskirts. I would never have learned that if I hadn’t spent time on the outskirts myself.”

Parents also report that in their gap-year lives, they had time and freedom to mitigate issues such as homesickness. Huston notes, “Because Sherry and I weren’t working, we had tons of time to scheme to make the kids’ non-school hours really wonderful.”

And Sally feels like the challenges of her time in Peru have given her a giant new appreciation of home. When asked what she and her brother were most thankful for on their return, Sally and Sam chime at once, “Hot showers!”

Gratitude is another lesson that’s hard to lecture our kids about; it’s unlikely that any of us could talk our kids into being grateful for the hot-water heater. But when they live somewhere without one? No reminder required.

Deciding to quit that job or take a leave, renting the house on Craigslist, signing kids up for school and figuring out the money: Taking your family out and away presents honest-to-goodness, sometimes scary challenges.

But here’s another challenge: living in an American city in a house that has more people than bedrooms and trying to convince the children that this fact alone does not make us underprivileged.

Stamps in a passport are hardly requirements for growing qualities such as independence, problem solving and awareness of our place in the world, or for an unshakeable closeness within the family. But when the families in this story took themselves away to another life, another culture, they found that many of those gifts just kind of happened.

Who would have guessed that this kind of adventure, this time out of time, would turn out to be the easiest, most direct way to teach some of the values and life skills we desperately want to give our kids?

In a new life, in an unfamiliar culture, families live the lectures instead of having to speak them. That part, it turns out, is not hard at all.

>>Next: How'd they do it? The Eastland-Fruit family

SKIP AHEAD: Mind the gap: Resources for planning

How’d they do it?

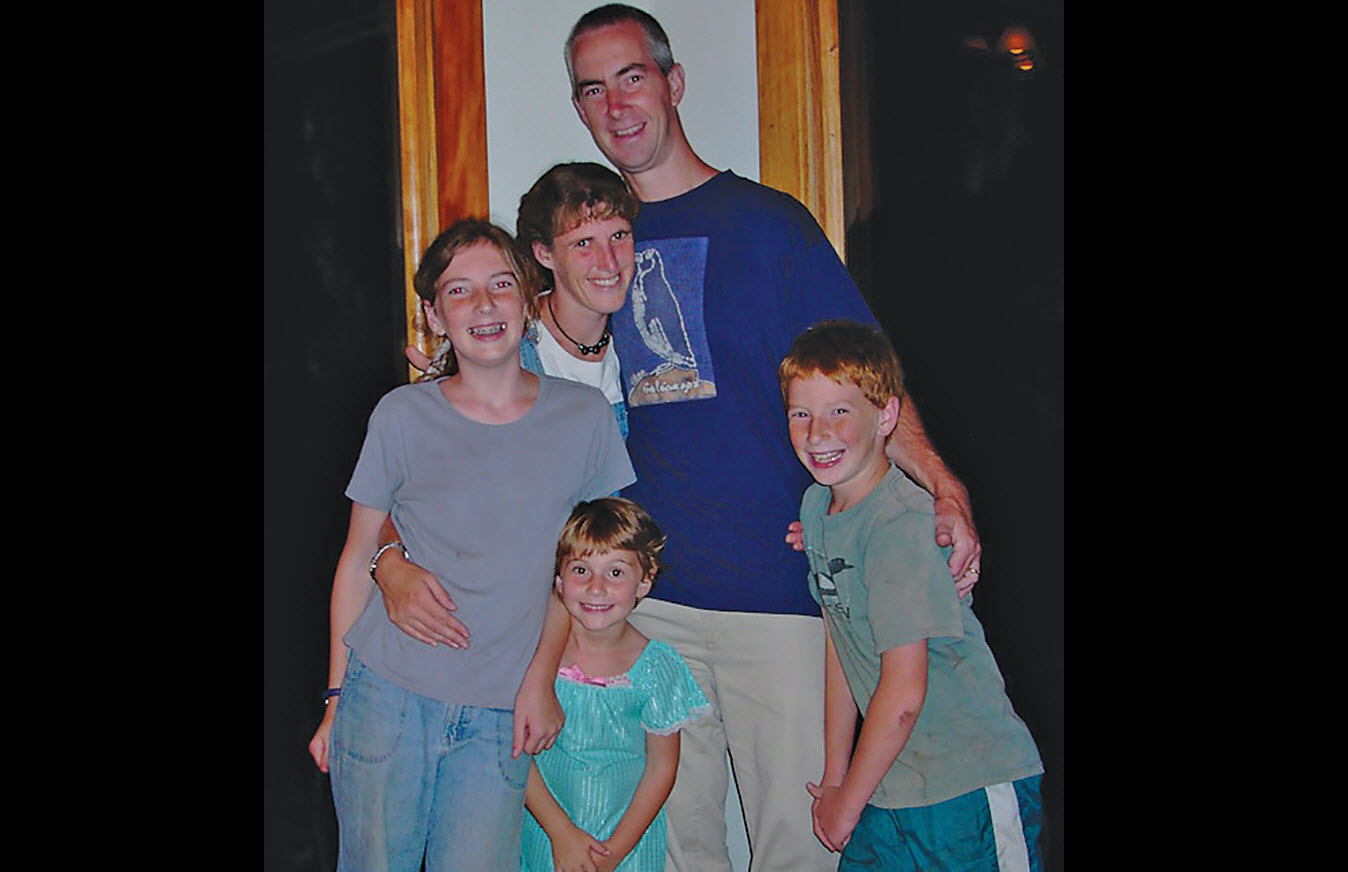

The Eastland-Fruit family

Chris Eastland, Dianne Fruit, Ridley and Rory | Home: Kenmore, Wash.

Where did they go? Costa Rica (two and a half months) and shorter stints in various places in South America and Europe. The whole family volunteered at a sea turtle conservation camp, and Fruit and Eastland also volunteered at the school Ridley and Rory attended in Costa Rica.

For how long? Six months total

How old were the kids? Ridley, 13; Rory, 10

How did they manage school? Two months at a dual-language school in Costa Rica; other than that, learning on the go

How did they manage work/money? Fruit had a paid sabbatical from her job as a community college instructor; Eastland took unpaid leave from his job as an engineer. Both were able to return to their jobs.

Most surprising aspect? Fruit: “When we returned, I found it hard to adequately summarize the trip when others asked about it. We had experienced so much! Even though I’m well versed in reentry shock, I was bewildered about how to return to our ‘normal’ lives and at the same time incorporate how I had changed and grown.”

Most lasting effect: Languages; willingness to try new things; new awareness of need versus want; new friends

Any advice?

Rory: “Don’t take everything so seriously.”

Ridley: “Pack light. Be willing to go with the flow when necessary. Record everything (write stuff down, take videos and audio recordings to capture how things were at the time).”

>>Next: How'd they do it? The Richards-Steel family

BACK: The Family Gap Year + family profile index

SKIP AHEAD: Mind the gap: Resources for planning

How’d they do it?

The Richards-Steel family

Bill Richards, Ashley Steel, Zoey and Logan | Home: Bellevue, Wash.

Where did they go? Vienna, Austria

For how long? Six months

How old were the kids? Zoey, 8; Logan, 5

How did they manage school? The girls went to an international school in Vienna.

How did they manage work/money? Steel’s Fulbright Fellowship took them to Vienna, where they both continued working as professional ecologists.

Most surprising aspect? Steel: “How much family time there is when you take away your regular routines. The kids still had playdates, homework and after-school classes, but we ended up with special time together in the apartment, waiting in restaurants, visiting museums, navigating public transportation, getting lost or exploring on purpose.”

Most lasting effect: “The two biggest are: a family identity built on multicultural exploration, and a set of friends in other countries that continue to enrich our lives.”

Any advice? “Go slow! Traveling fast, you can skim the surface of a large number of places as a tourist. Slowing down, you can see things through new eyes, be open to the unexpected and start to understand other world views.”

>>Next: How'd they do it? The Page-Salisbury family

BACK: The Family Gap Year + family profile index

SKIP AHEAD: Mind the gap: Resources for planning

How’d they do it?

The Page-Salisbury family

Margot Page, Anthony Salisbury, Hannah, Harry and Ivy | Home: Seattle, Wash.

Where did they go? Monteverde, Costa Rica

For how long? 12 months

How old were the kids? Hannah, 12; Harry, 9; Ivy, 5

How did they manage school? Inexpensive (by U.S. terms) private school that draws students from the local community, but welcomes international kids

How did they manage work/money? Salisbury and Page both quit their jobs. With no salary income, they lived on the $800 difference between the mortgage payment on their Seattle house and the amount they were able to rent it for. Leaving wasn’t scary at all, but the idea of coming back with no jobs and no rental income was. Both are again employed.

Most surprising aspect? Salisbury: “Life takes longer without U.S. efficiencies: making breakfast, shopping, making dinner, etc. And efficiency is overvalued.”

Most lasting effect:

Salisbury: “Rich is a state of mind. And a realization that cars are nearly unnecessary in an urban setting.”

Harry: “I learned Spanish and kept it. :) Everyone else is jealous. :)”

Ivy: “I feel way closer to my siblings than I think a lot of my friends feel, and I think we have that year to thank.”

Any advice?

Page: “If your kids are old enough to have opinions, get their buy-in. Every hard moment is made better when everyone wants to be here.”

Salisbury, Hannah and Ivy: “Why are you still sitting there? Go. Stop considering, start packing.”

>>Next: How'd they do it? The Smith-Huston family

BACK: The Family Gap Year + family profile index

SKIP AHEAD: Mind the gap: Resources for planning

How’d they do it?

The Smith-Huston family

Sherry Smith, Matt Huston, Sam and Sally | Home: Seattle, Wash.

Where did they go? Cajamarca, Peru

For how long? Six months

How old were the kids? Sam, 12; Sally, 10

How did they manage school? Inexpensive (by U.S. terms) private school that drew from the local community. Sam and Sally were the only non-Peruvian kids in their school.

How did they manage work/money? Huston, a middle-school teacher, was granted a paid sabbatical with a “deliverable” to complete a study of Peruvian cookery. Smith quit her job as an exhibit writer at a design firm. “That was six months of stress,” says Huston of Smith’s job search on their return.

Most surprising aspect? Huston: “Not missing other Americans. We chose an out-of-the-way, not touristy place and never regretted it.”

Most lasting effect: Smith: “A sense from the kids that they can handle a lot. They’ve been through some challenging situations, and it was hard and interesting. And they want to go back.”

Any advice? “It’s more work than you think to get out the door.”

>>Next: How'd they do it? The Chen-Carlin family

BACK: The Family Gap Year + family profile index

SKIP AHEAD: Mind the gap: Resources for planning

How’d they do it?

The Chen-Carlin family

Sharon Chen, Peter Carlin, Lucy and Leo | Home: Seattle, Wash.

Where did they go? Taipei, Taiwan

For how long? Two years

How old were the kids? Lucy, 5; Leo, 3

How did they manage school? Both attended a private school with classes taught completely in Mandarin.

How did they manage work/money? Carlin, a manager in high tech, was able to get a job that moved him to Taipei. Chen was an at-home mom, as in the states.

Most surprising aspect? Chen: “One thing that surprised me was the anxiety around second-guessing myself in the early weeks. There was a difference between the intellectual plan of moving for intangible benefits and the reality of staring it in the face. I remember walking around the city after dropping my kids off, thinking, Is this just me being selfish, wanting to travel and being ‘worldly,’ whatever that means? What if my daughter doesn’t learn the language quickly?”

Most lasting effect: “Besides the obvious lasting effect of facility in a language besides English, the increased flexibility in palate.”

Any advice? “Make sure both partners are excited and willing to do it.”

>>NEXT: Mind the gap: Resources for planning

BACK: The Family Gap Year + family profile index

Mind the gap: Resources for planning

Getting away can be as simple as renting out your house and buying some airplane tickets. But for help with the pesky logistics, check out:

The Career Break Traveler’s Handbook and website. Jeff Jung offers practical advice on dreaming and planning extended travel.

Family on the Loose book and website. Ashley Steel and Bill Richards share what they’ve learned in their years of traveling with their kids.

Wandermom. Inspiration for where to travel with children

Transitions Abroad. A travel resource for meaningful work, living and study abroad

Paradise Imperfect: An American Family Moves to the Costa Rican Mountains. Margot Page’s unvarnished chronicle of what happened to her own family (and marriage and attitude) when they took a gap-year adventure. margot-page.com

Expat websites worth checking out include The Displaced Nation, Overseas Radio and The Emotionally Resilient Expat.

*Pictured: The Eastland-Fruit family

BACK: The Family Gap Year + family profile index