Photo:

While specific lessons about the Holocaust generally start around fifth grade, conversations to prepare young children to learn about the Holocaust can begin years before they know about WWII. Photo: Jenna Vandenberg

Talking about the Holocaust is challenging for parents and educators who don’t want to sugarcoat history, but are wary of presenting stories of unimaginable suffering to children. Often, parents choose silence; it’s easier to avoid tough topics or save them for a nebulous later date.

But we must remember history.

Misinformation, Holocaust denial, antisemitism and general apathy are chipping away at efforts to teach, learn and remember this time in history.

Jan. 27 is International Holocaust Remembrance Day. It’s the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. So on this anniversary, let us remember the 6 million victims of the Holocaust. But also, let us reflect on how to teach new generations about this history of Nazi persecution and antisemitism.

Our ability to combat hatred and promote human dignity depends on it.

Living history makes an impression

Last year, the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial Foundation brought survivors back to Poland to visit the site of their incarceration and liberation. They walked the grounds with their families. They remembered. They asked others to remember.

Six years earlier, the foundation’s trip included over 120 survivors. Last year, only 18 survivors made the trip.

Now the ABMF takes teachers to Poland, and I was honored to go as a teacher fellow last summer. We heard from Holocaust survivors, museum guides, Jewish leaders and educators at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial. Every time they spoke, a deep and passionate sense of historical urgency tinged every syllable of their stories, speeches and answers to questions.

Soon, there will be no more survivors. There will be no more white-haired elders to recall the walk to the Kraków ghetto, to describe the train ride or the smell of the gas chambers. The only ones left to tell those stories will be … us.

All of us.

While specific lessons about the Holocaust generally start around fifth grade, conversations to prepare young children to learn about the Holocaust can begin years before they know about WWII. These simple suggestions can help parents talk to kids of any age about this important historical event.

Toddler–pre-K: Learning about identity and celebrating differences

Branda Anderson, the Teaching and Learning Specialist at The Holocaust Center for Humanity in Seattle, recommends that parents and caregivers talk about identity and “othering” with very young children.

“Begin with conversations about your child’s own identity,” Anderson says. Explain that identity is all the things that make you unique: your memories, experiences, people you know and things you care about. “Have them think especially about parts of their identity that cannot be seen,” Anderson suggests. For example, your child may be a sibling or someone who loves camping.

Then, ask about the identity of others. Talk about family friends, sports stars or characters in movies. Compare identities and celebrate specific differences between your child and others.

“The goal at this stage is to understand that identity is made up of many things. Kids should be encouraged to see differences as interesting, not threats,” Anderson says.

Some parents shy away from talking about differences between people, but discussing differences helps kids appreciate diversity and when they are older, they’ll be better able to recognize discrimination when they see it.

Grades K–2: Adding ‘othering’ to the conversation

At this age, kids start to see and understand that people can be treated differently based on their identity. School might be the first place where students interact with people from a variety of different cultures and religious backgrounds. Sadly, it might be the first place where kids see or experience social exclusion.

Therefore, it’s important to discuss that separating people into groups based on identity can sometimes be harmless (e.g. grade levels), but it can also be dangerous if people are treated differently based on the group they have been placed in.

“It’s important to go beyond simply telling kids it’s ‘not nice,’ to exclude people,” Anderson stresses. “Kids should learn that treating people like they don’t belong, or excluding people because of differences goes beyond politeness. It is harmful, wrong and dangerous.”

Grades 3–5: Connecting identity and ‘othering’ to oppression

At this age, kids are ready to learn how some groups of people are treated unfairly in a pattern of mistreatment. This is an appropriate time to teach kids about concepts like racism and antisemitism through individual stories and examples. You can point out examples in books and movies of groups of people being treated unfairly. Kids are beginning to absorb the news in upper elementary grades. If your child is used to discussions about identity and othering, it can provide a useful lens through which to discuss current events and politics.

Fifth grade is when students often start learning about the history surrounding the Holocaust. If you are teaching at home, avoid trivializing Holocaust history. Coloring pages, word searches and gimmicky quiz games are not appropriate ways to teach or talk about the Holocaust in most cases. Also, guard against simplifying or glorifying history. Remind kids that every single person in history made choices for a variety of different reasons, and everyone’s experience of WWII was different.

Several books for this age discuss the Holocaust and the extreme antisemitism of the Nazis through one specific character (see list below). The 10-minute video “Remember the Children: Daniel’s Story” from The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is a good starting point as well. It’s intended for kids in grades 4 and older.

Grades 6–8: Connecting stories of oppression to history

A mere decade ago, nearly every young teenager knew the basics about the Holocaust thanks to a plethora of books and movies on the subject, family members who’d fought in WWII, and a robust history curriculum. Today, most WWII veterans and survivors have passed on, teens are more likely to turn to social media for entertainment instead of Steven Spielberg films, and curriculum has shifted. Increasingly, kids are leaving eighth grade knowing nothing about the Holocaust.

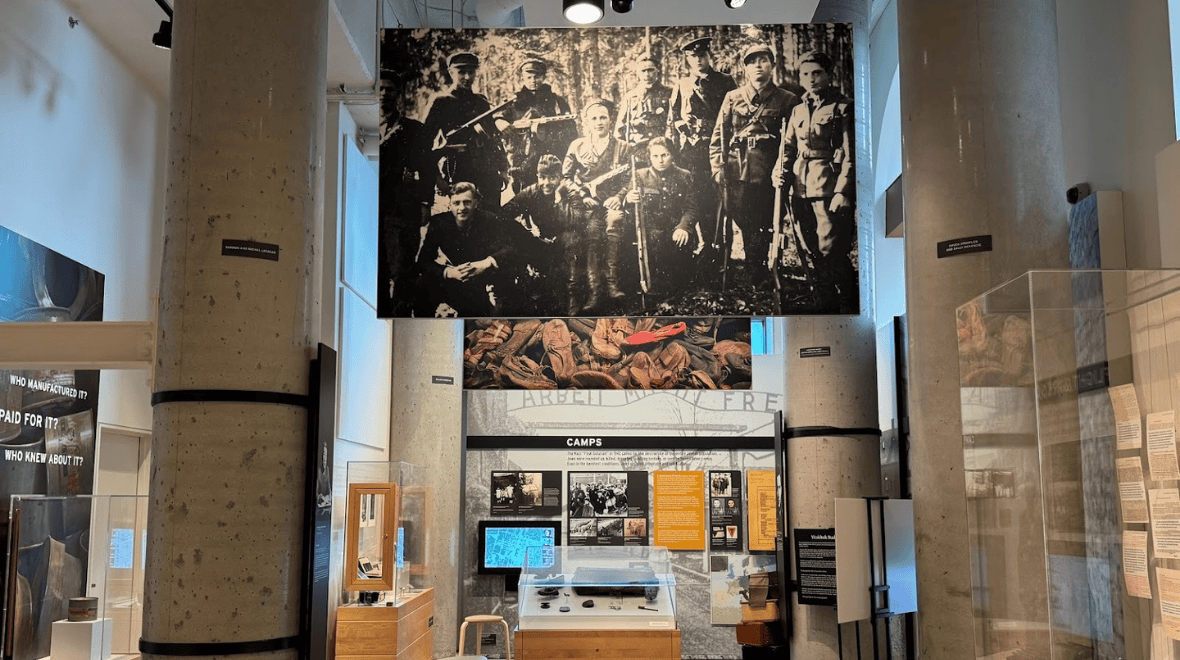

The Holocaust Center for Humanity in Seattle can help. Tucked between Pike Place and Belltown, the museum is the epicenter for Holocaust education in the Greater Seattle area and is an excellent resource.

The museum was intentionally designed with families in mind, so no visuals are displayed that will horrify young children. More disturbing images are behind panels that patrons can choose to view.

If your child knows the basics about the Holocaust, they’ll get more out of the visit. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has both an article and a film about the Holocaust that give thorough overviews.

As you talk about the Holocaust with this age group, strive to use precise language. Use the phrase “Nazis and their collaborators” instead of “Germans.” When discussing the locations of concentration and death camps, remember they were located in Nazi-occupied Poland, not the sovereign nation of Poland.

In a similar vein, do not characterize Hitler as a “monster” or “lunatic.” Hitler was a human, responsible for evil deeds. We as humans are still capable of bigotry and othering. Referring to Hitler as a monster takes away this burden of humanity.

The Holocaust Center for Humanity has a 25-minute film that features local survivors. These can be great entry points for children to learn about the Holocaust, but survivor stories can be tough to hear. “Think about how your child does with sad books and movies,” suggests Anderson. “If they don’t do well with those, they likely aren’t ready for survivor stories.”

While at the museum, be sure to ask questions and talk with docents and museum staff. Interact with the multimedia display about local families who survived the Holocaust. Their stories and paths to Seattle are shared via digitized photographs, maps and information. Spend time at the Architecture of Atrocity installation. The piece shows how harmful stereotypes can lead to escalating hate in the form of bullying, discrimination, violence and genocide.

After your visit, ask your kids open-ended questions about what they experienced at the museum. “Try to avoid summarizing the visit or sharing your own takeaways,” Anderson suggests. “Get your kid’s thoughts first. Let them process the visit before hearing your thoughts.”

Grades 9–12: Connecting history to the present

High school students will likely learn about WWII and the Holocaust in school, so this is a good time to encourage them to think about the complex layers of this history through discussions at home. Teens can reflect on how the Holocaust is taught, how we remember the Holocaust, and why it’s important to learn about history. Teens have likely heard survivor stories. Remind them that survival was the exception. Most Jews who were sent to camps were not rescued and did not survive. They died.

Social media and AI have also complicated the landscape. AI-generated images purportedly showcasing Holocaust survivors are flooding the internet. Antisemitism has historically been fueled by conspiracy theories, and conspiracy theories tend to get a lot of traction on social media apps. This has led to a resurgence of some dangerous myths.

As always, the best way to combat disinformation and social media issues is to open up conversations. Search “Auschwitz” on social media with your teen, and ask about which selfies and videos they think are appropriate to share and which are not. This typically leads to a nuanced conversation about the challenges with how we remember and honor Holocaust victims. Remember to let your child do most of the talking.

The Center hosts a few opportunities for older students to get involved. There is a yearly art contest for students in grades 5–12 (submissions are due March 27), and a student leadership board for students in grades 7–12. The student board members meet twice a month and serve as ambassadors and volunteers for the Center’s events and programs.

About the Holocaust Center for Humanity

Museum educators and managers at the Holocaust Center for Humanity serve the public not only by curating and showcasing artifacts and local stories about the Holocaust, but they also host field trips, organize community programs, train teachers and law enforcement officers, serve 167 school districts in Washington, and maintain a bureau of speakers. Seattle-area Holocaust survivors and their families frequently speak at the Center.

The museum frequently hosts school field trips, and is also available for homeschool groups and groups of families.

The museum is open on Sundays from 10 a.m.–4 p.m., and first Thursdays from 4–7 p.m.

Recommended reading

Toddler–pre-K:

- “Rising” by Sidura Ludwig and Sophia Vincent Guy

- “Bilal Cooks Daal” by Aisha Saeed and Anoosha Syed

- “Lovely” by Jess Hong

Grades K–2

- “The Day You Begin” by Jacqueline Woodson and Rafael López

- “The Tree of Life: How a Holocaust Sapling Inspired the World” by Elisa Boxer and Alianna Rozentsveig

- “My Name is Not Refugee” by Kate Milner

Grades 3–5

- “Number the Stars” by Lois Lowry

- “Refugee” by Alan Gratz

- “The Length of a String” by Elissa Brent Weissman

- “More Than Any Child Should Know: A Kindertransport Story of the Holocaust” by Paul Regelbrugge, Julia Thompson and Sean Dougherty

Grades 6–8

- “The Diary of a Young Girl” by Anne Frank

- “The Boy on the Wooden Box” by Leon Leyson, Marilyn Harran and Elisabeth Leyson

- “Alias Anna: A True Story of Outwitting the Nazis” by Susan Hood and Greg Dawson

- “White Bird” by R.J. Palacio with Erica S. Perl

Grades 9–12

- “Night” by Elie Wiesel

- “Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale” by Art Spiegelman

- “Games of Deception: The True Story of the First U.S. Olympic Basketball Team at the 1936 Olympics in Hitler’s Germany” by Andrew Maraniss

- “Under the Same Stars” by Libba Bray

Jenna Vandenberg is a mom and high school history teacher north of Seattle. She is a teacher fellow with the Auschwitz Legacy Fellowship, a flagship program of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial Foundation and the Holocaust Center for Humanity.