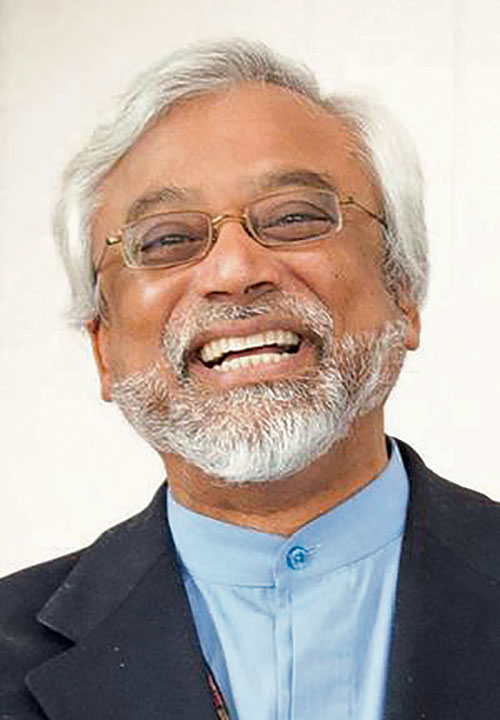

We all want our children to grow into adults with strong moral compasses, yet how do we teach them to be nice, kind and caring? Our kids won’t do right just because we tell them to do it, so for guidance that might light the way for us (and help unite us after a divisive political season), we brought our questions about raising empathetic children to four local religious leaders. We spoke with Rabbi Rachel Nussbaum from Kavana Cooperative, a nondenominational Jewish community group on Queen Anne; the Rev. Bryan Dolejsi, parish priest at St. Benedict Catholic Church in Wallingford; Imam Jamal Rahman, a Muslim Sufi minister at Interfaith Community Sanctuary in Ballard and an “Interfaith Amigo”; and Anita Feng, a Zen Buddhist master and guiding teacher at Blue Heron Zen Community in Northgate.

Children naturally gravitate toward stories, routines and rituals. Organized religion is just one way that people find connection and a way to ground individual stories within a bigger story, says Nussbaum. Parents can create their own traditions, drawing (if they like) on religious frameworks. For example, the Jewish Shabbat dinner often becomes the basis for a weekly family check-in that includes sharing highlights or “gratitudes.” In the following interviews, you’ll find more ideas from traditions and practices that speak to the complicated world we live in today.

Within our current political climate, it’s helpful to remember that listening matters. What role does your religious tradition play in listening, uniting and connecting?

Feng: Practicing meditation teaches us what goes on in the head and the heart, yet meditation is a 24/7 proposition. We use the acronym FACE: ‘focus’ on counting our breaths; ‘accept and acknowledge’ the present moment; ‘clear,’ as in let it go; and ‘engage’ now in reality in a helpful way. We can teach our children to accept what is being experienced right now. It’s up to us — within our families first — to let it go and be clear.

Dolejsi: I encourage people to pray for wisdom: knowing what to do and when to do it, what to say and when you say it. We can have disagreements, but we are not called upon to disagree — we are called on to be charitable. A heated exchange isn’t the most prudent time to speak your truth. We need to dialogue from a calmer place of respect with each other.

Rahman: Every religion states a person’s behavior might be unacceptable but his or her essence is sacred. Protect yourself. Don’t allow yourself to be abused. But as you take the right action, remind yourself the person’s being is divine. This discernment can shift heaven and earth. In South Asia, people often say the best way to overcome polarization is to share three cups of tea: listen, respect and connect.

Nussbaum: My Rosh Hashanah sermon was about training ourselves to listen to voices that are harder to hear, the ones that push against the grain. This summer while I was in Israel, I spent time in the West Bank meeting with Palestinians because I want to understand a perspective that I had heard less of. Listening and connecting starts really small: Help kids think about how they interact with their siblings, other relatives, teachers and friends.

How does your community discuss the issues that are causing tension in America: violence, racism, sexism, exclusion of immigrants, etc.?

Feng: Our religious community meets weekly to talk about issues within our community and world, knowing these issues are based on dualistic thinking. We practice applying mediation techniques to our dialogue, remembering our common humanity and using love and compassion. Yet as we talk, it doesn’t take long for dualism to creep in!

Dolejsi: I like to give ways to focus prayer not only on people who are experiencing difficulties, but also on those who are perpetrating violence. Because we ourselves need constant conversion, we shouldn’t look down on others; instead, accompany people along the way. We are all called upon to take care of each other.

Rahman: The Quran says that God has created diversity for one primary reason: that we might come to know the other on a human level in spite of our differences. Can we share human stories? Can we listen to the other? Do we listen to our children and allow them to ask difficult questions, including those on religion?

Nussbaum: In the Talmud, we learn all human beings were created in God’s image from a single human being to teach us a lesson. No one can say my ancestors were greater than your ancestors. When confronted with societal issues, I guide my community to look at others and try to see the essence of God in them.

From the perspective of your religious tradition, what everyday actions lead to better connections between people?

Feng: Using FACE in everyday interactions leads to better connections. Take a pause to breathe, accept and acknowledge what’s happening right now, clear and let go of what isn’t helpful and then engage in what’s happening right now.

Dolejsi: I encourage parents to pray with their kids in a simple way: blessing meals, and prayers in the morning and before bed. We pray for what we need and then move outward, praying for others. Parents can pray with their children in a way that feels right to them, whether that’s praying the rosary or meditating.

Rahman: Gratitude opens the heart and increases the capacity to love God’s creation. Children are taught to touch their heart to express thanks for blessings little or big. This practice connects us to the Source of love and compassion: God resides in every human heart. By connecting to the Source in gratitude, we are humble and kind with others.

Nussbaum: Prayer (or reflective moments) can be a powerful practice for kids and parents to do together. In the Jewish tradition, we say a prayer of gratitude upon waking up, thankful for another day of life. We also pray at bedtime, and this prayer is about forgiveness, release and winding down. We think, ‘Tomorrow I will try to do better and be the best person I can be.’

What are the best values and virtues that come out of being part of your religious tradition?

Feng: In Zen Buddhism, our most important direction is to help everyone awaken to their own realized self. As a Zen teacher, I say don’t be attached to words, which are a finger pointing at the moon. The moon is the metaphor for awakening, which can happen in a moment and then in another moment. In these moments, dualistic thinking disappears as we feel our oneness. From here, it’s possible to be of service to others.

Dolejsi: The foundational starting point for us is that we’ve been loved by God. From that full place, we can love and serve other people. Our good acts are not based on self-worth, productivity or trying to be better than anybody else.

Rahman: Islam’s main spiritual teaching is to practice compassion for self and others. With sacred naming, children choose a word or sentence to use with their names that evokes compassion. I chose ‘Brother Jamal.’ When I am self-critical, I do a spiritual intervention by saying, ‘But Brother Jamal.’ Immediately the energy changes; a negative inner conversation becomes merciful and gentle.

Nussbaum: Our most fundamental Jewish values stem from the story that our ancestors were once slaves in Egypt, so we can relate to being the underdog. Biblical texts instruct us to take care of the ‘widow and the orphan,’ but today I would extend that obligation to trying to help anyone who is vulnerable in our society.