I am a 65-year-old Black man in America. I have been a criminal defense attorney for more than 40 years. So, I have seen my fair share of racism. But it wasn’t until 2011, when my wife and I became parents, that I had to face the reality of how much I still didn’t know about this country’s history and its impact on racial progress today.

That year, my sister-in-law passed away, and we became the caregivers of her then-13-year-old son, our nephew Matthew. All of a sudden, we were responsible for raising a young Black child, and the surface skimming that I felt like I had been doing on the history of race and what racism means in America felt like it wasn’t enough.

So, I started reading more. And I found myself getting angry and feeling ignorant. I attended Marquette University and graduated from Harvard Law School. I’ve had one of the best educations available in America, but I started learning things about the history of race in this country that I never knew before. I thought, How could I not have known this? How could I not have been taught this? And I started thinking, If I don’t know this, I wonder how many other people don’t know.

It turns out that it’s a lot. According to a 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center survey of high school seniors, fewer than 1 in 4 students can correctly identify how provisions in the Constitution of the United States gave advantages to slaveholders. Two-thirds of Americans don’t know that it took a constitutional amendment to formally end slavery for most Black people, except for those convicted of a crime. Only 8 percent of high school seniors can identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War. Many white Americans still haven’t heard of the Tulsa Massacre, and the majority don’t know about similar tragedies in Wilmington, Elaine, Colfax, Memphis and Pulaski.

And yet, as we have conversations about how to better educate young people on our history, somehow “making white kids feel bad” has become a rallying cry to censor their learning. In 29 states, legislation has been proposed to limit what educators can teach related to this country’s racist history. In Tennessee, legislators are working to make it legal to impose fines ranging from $1 million to $5 million on teachers who knowingly teach concepts such as systemic racism — all under the guise of protecting white kids.

But what will this accomplish? Pretending that this country is or has ever been colorblind dismisses the experiences of Black, Indigenous and other children of color and centers white kids’ feelings over truth. While developmentally appropriate and trauma-informed teaching is important for all kids, kids’ “feelings” about historical events and verifiable facts should not excuse them from learning about them.

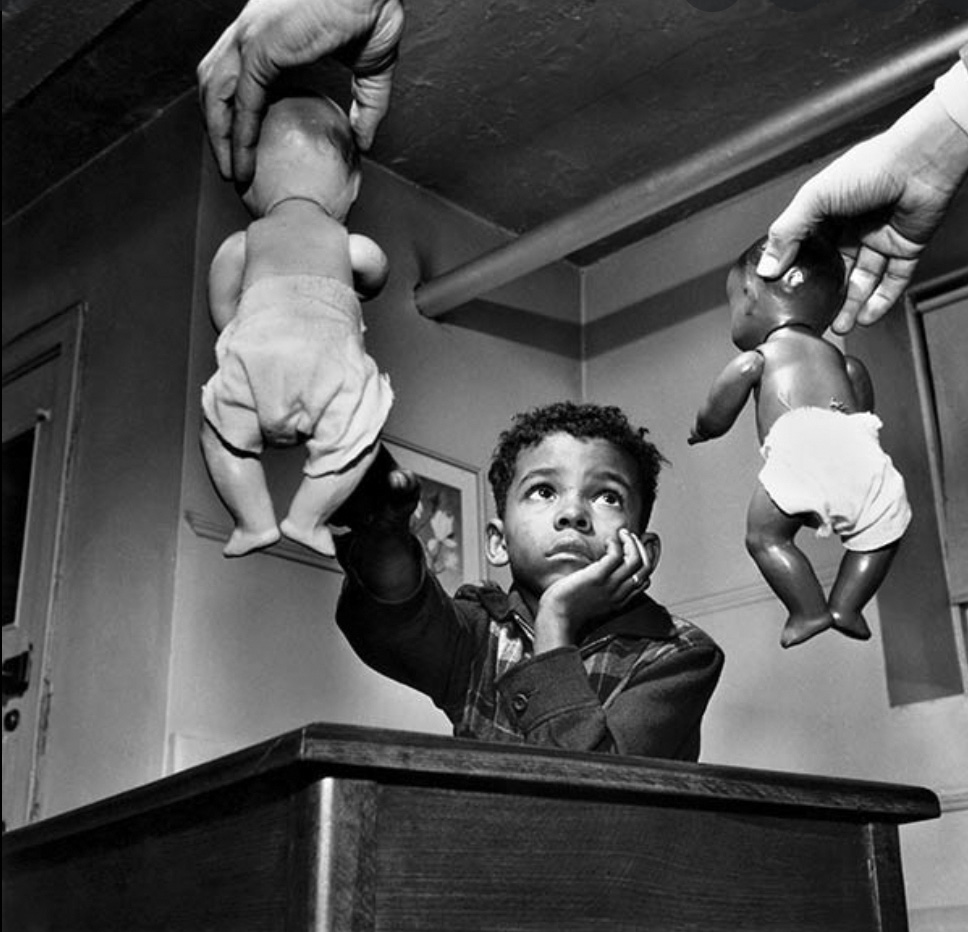

In the landmark “doll test,” Black children were presented with dolls with different skin colors. “Fifty-nine percent indicated that the brown doll ‘looks bad.’” The experiment was used during the Brown v. Board of Education hearing to demonstrate the impact of segregation on Black children. Photo: Gordon Parks, “Untitled, Harlem, New York,” 1947; courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Children are not colorblind. Even infants recognize racial differences. Furthermore, studies suggest that children develop racial prejudices early in life. By the time kids are toddlers, they’ve already learned to act out in racialized ways. In a 2003 study of more than 200 preschoolers, developmental psychologist Phyllis Katz discovered that when 3-year-olds were shown photos of children of different races and asked to choose whom they might like to be friends with, one-third of the Black kids chose only photos of other Black kids. Eighty-six percent of the white kids in the study only chose photos of other white kids.

Children pay attention to the world they live in and make assumptions about why things are the way they are.

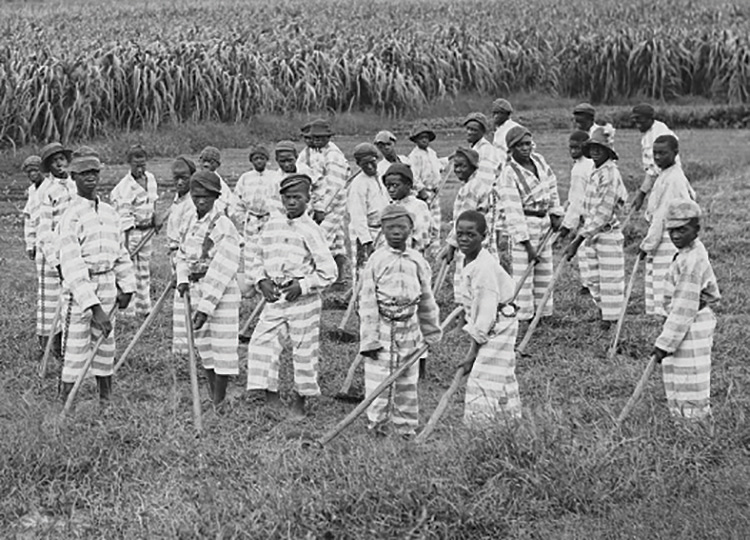

When we minimize the impact of slavery, Jim Crow and the school-to-prison pipeline, we teach kids that the current disparities that exist among Black and white folks are just the unfortunate consequences of an individual’s or community’s poor decision making. They may (and do) wrongly conclude that there are no systemic reasons for the racial disparities that exist in everything from education to wealth, infant mortality and criminal justice outcomes. They may (and do) wrongly blame those most oppressed by past and present racist policies, institutions and practices, and in doing so perpetuate more racist policies, institutions and practices.

They see race and they learn racism unless we choose to teach them something different.

We don’t teach history because it’s fun — or even entertaining. We don’t teach it to bolster kids’ self-esteem or to perpetuate any myth of their individual or their country’s exceptionalism. We teach history because “those who don’t know history are destined to repeat it.” If we want to raise critical thinkers, engaged citizens and moral people, we have to teach the truth about our history to all students. And the truth is: Genocide, human trafficking and enslavement are a part of our nation’s history. Learning about them — and the hate and opportunism that inspired them — is essential to making progress as a nation.