It is a cold January night along International Boulevard south of Seattle. The lights from nearby Seattle-Tacoma International Airport cast a foggy, yellow-gray glow over the highway as Detective Brian Taylor’s unmarked car crawls slowly from one abandoned parking lot to the next. The King County Sheriff’s officer tries to stay hidden; he is searching the dark sidewalks for underage girls who work this street, and the men who control them and buy sex from them.

It is a cold January night along International Boulevard south of Seattle. The lights from nearby Seattle-Tacoma International Airport cast a foggy, yellow-gray glow over the highway as Detective Brian Taylor’s unmarked car crawls slowly from one abandoned parking lot to the next. The King County Sheriff’s officer tries to stay hidden; he is searching the dark sidewalks for underage girls who work this street, and the men who control them and buy sex from them.

Finally, Taylor spots a petite girl with a round, young-looking face tucked into the furry hood of a black, cropped jacket. It is 9 p.m.; there is not much along this stretch of road but motels, strip malls and fast-food restaurants. The girl walks alone for 30 minutes, occasionally looking at her phone. She stops for 10 minutes in a dark lot, waits, then keeps going.

She has all the signs, Taylor says, and he thinks she will soon be picked up by a man. When she is, Taylor and his partners, in other unmarked cars nearby, hope to pull them over. For the “john,” it would be the worst turn of events; for the girl, likely a teenager, it could be the only contact she has for weeks, or months, with someone who can help her. If he talks to her, Taylor will slip the girl a card and tell her, “We have a place you can come.”

But as Taylor, slowly tracking the girl’s progress down the highway, pulls into a dark lot a block ahead of her to wait, he suddenly senses something is wrong. Behind him, out of sight for a few seconds, the girl has stopped, and a car that had been heading up the road just before is now missing. By the time the officers maneuver back to where the girl had been just moments ago, it’s too late.

Like vapor, she’s gone.

Anybody’s child

Experts estimate there are anywhere between 300 and 500 youths involved in minor sex trafficking in Seattle at any given time, most of them girls, but some are boys. National estimates indicate 100,000 domestic minors are trafficked within our nation’s borders.

But the true number, at least locally, is likely much higher. Because even as awareness of human trafficking grows, the commercial sex market — driven by technologically savvy and seemingly anonymous customers, and ever more financially and psychologically shrewd pimps — has stealthily moved from the exposed and unsophisticated arena of the streets to the more hidden quarters of text messages and private chat rooms on the Internet.

“It’s hard to track because it’s so clandestine,” says Melinda Giovengo, executive director of YouthCare, a major player in a recent, progressive collaboration to halt sex trafficking of youths in the state. YouthCare runs The Bridge, the only Washington state program providing long-term housing and wraparound services to sexually exploited youths in addition to emergency shelter.

Domestic minor sex trafficking (a term preferred over “prostitution,” which advocates say implies choice and belies exploitation) fits into the larger web of international human trafficking, which the United Nations estimates is a $32 billion industry that encompasses sex and labor slavery across the globe.

The average age of entry into the commercial sex trade is 13 years old, experts say. Of 459 investigated and confirmed U.S. sex trafficking victims from 2008 to 2012, more than half were 17 or younger, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

Sometimes, lives are lost. In 2009, just weeks after testifying as a star witness to a federal grand jury against the 36-year-old pimp who, she told police, lured her into prostitution when she was a 16-year-old high school sophomore, a girl from Everett with green eyes named Kelsey Collins vanished. Her case remains unsolved.

Children who end up being sexually trafficked often have predictive factors in their past. The two most common factors: They are runaways and victims of childhood sexual abuse, says Leslie Briner, sexual exploitation training and policy coordinator at YouthCare.

Though not a direct correlation, childhood sexual abuse causes “early sexual debut” — an early awareness and a susceptibility to further victimization “that pimps smell a mile away,” says Briner.

But it’s not only troubled kids who become victims, experts warn.

“Two loving parents. Affluent household. Good grades. All it takes is for a girl to have a bad day, a self-esteem issue. A guy approaches her at a gas station and, boom, she’s working,” says Sgt. Jaycin Diaz of Seattle Police Department’s (SPD) Vice and High Risk Victims Unit.

“The grooming process happens in malls, schools, sometimes by other kids. The pimps are more business-minded.”

Downtown Seattle’s Westlake Center mall is one of the most popular pickup spots, police say. So are public buses, where a well-put-together pimp might compliment a girl on her gorgeous eyes. If the girl blushes, looks down, doesn’t respond in a powerful voice — psychologically, she’s an ideal victim, advocates explain.

“These girls think they are getting romanced,” says Taylor, a detective with the King County Sheriff’s Street Crimes Unit. “Parents need to understand: It can happen to anybody’s child.”

‘No one is consenting’

In the early ’80s, the issue of exploited minors gained national attention. But soon after, federal money for housing and intervention ran dry. “For 25 years, we stalled out,” says Giovengo.

In 1995, Washington state passed the Becca Bill, named after 13-year-old runaway Rebecca Hedman, who was killed by a man who paid her $50 for sex. The bill allowed parents of at-risk youths to intervene for the protection of their children.

Then, in 2000, the federal Trafficking Victims Protection Act passed, qualifying minors used in commercial sex as victims of domestic minor sex trafficking. Some crucial state legislation followed. In 2007, an FBI task force on sex trafficking was created in Washington state; soon after, Seattle leaders commissioned a study of children in prostitution.

Over the last three years, a constellation of state advocates, service providers, legislators, researchers, prosecutors, judges and law enforcement have united to address the issue of minors trafficked for sex and create solutions.

Because of increased efforts and awareness, you could say Washington state is just now coming of age on this issue — on the cusp of adulthood, but not yet out of the woods of adolescence.

New laws have passed — 18 since 2010, ranging from SB 6476, which strengthened penalties for the crime of commercial sexual abuse of a minor and required development of training for law enforcement officers, to SB 6255, which allows minors who are convicted of prostitution resulting from being trafficked by force, fraud or coercion to request the court to vacate the conviction. Funding is forthcoming; pimps are receiving harsher sentences; high-profile stings of pimps and buyers (formerly called johns) are making headlines.

New laws have passed — 18 since 2010, ranging from SB 6476, which strengthened penalties for the crime of commercial sexual abuse of a minor and required development of training for law enforcement officers, to SB 6255, which allows minors who are convicted of prostitution resulting from being trafficked by force, fraud or coercion to request the court to vacate the conviction. Funding is forthcoming; pimps are receiving harsher sentences; high-profile stings of pimps and buyers (formerly called johns) are making headlines.

Yet progress is still slow for many reasons, not the least of which is the stigma of a child being criminalized (erroneously and in conflict with state and federal laws, advocates point out).

“Even though it may appear willing or voluntary, [these kids] are doing it because they think they love someone,” Giovengo says. “They are victims. They have been threatened. They have been drugged. They have been manipulated. It is rape. Let’s be clear, no one is consenting.”

Victims or criminals?

Delving into the culture of sex trafficking of minors is like peering through the looking glass. Everything about this world, and the system in place that allows it to flourish, seems backward.

It is a world where code words and symbols dropped into texts, chat rooms and advertisements in publications like Backpage.com signal a prostitute is underage. It’s a world where the type of jacket a teenage girl is wearing, whether it has a fur-trimmed hood, might indicate that she is not walking to the movies or the grocery store, but instead is working the street.

It’s a world where businessmen traveling to Seattle for a convention might seek to buy 16-year-olds for sex, like a trip upgrade; where a cheap hotel room near Sea-Tac airport houses a family flying out early to Disneyland and next door hides a teenager earning $500 a night for her pimp.

Girls walk “the track,” finding buyers on the street or through digital connections. They often form what’s called a “trauma bond” with their pimps, who are in total control and almost always abusive, but who also act as a girl’s “boyfriend,” providing her with the only stability she knows, experts explain.

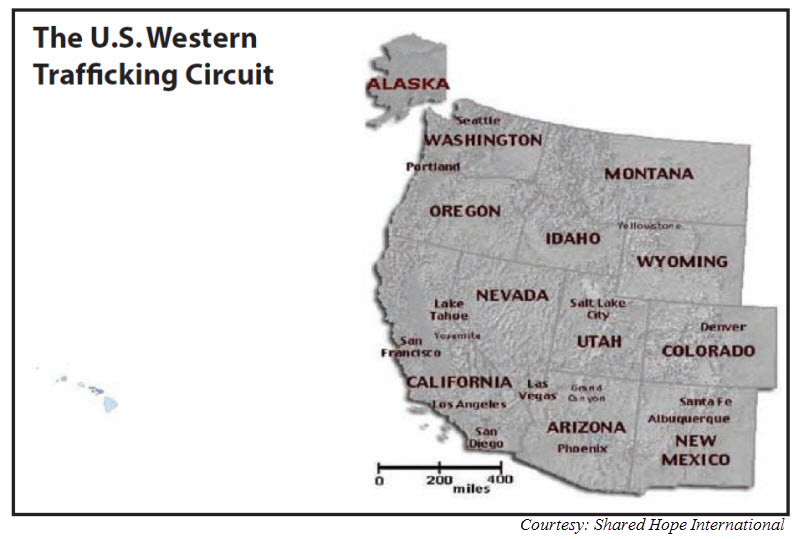

Pimps move victims along what’s known as a West Coast circuit: Vancouver, British Columbia, to Seattle, Portland, Sacramento, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix and Las Vegas.

Pimps move victims along what’s known as a West Coast circuit: Vancouver, British Columbia, to Seattle, Portland, Sacramento, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix and Las Vegas.

Removing a girl from her community isolates her, explains Noel Gomez, a former teen victim who is now a Seattle outreach expert.

“He took me to California, took my ID,” she says of her former pimp. “I was 16 and scared. I had nothing. I knew no one.”

Girls are also kept from bonding with each other, Gomez says. A common role is known as “bottom bitch” — a senior girl who helps control the others in exchange for a favorable position. If a girl “chooses up” — looks another pimp in the eye — that pimp can take her over as his own. It’s why girls often keep their eyes cast down.

But possibly the most backward detail right now in the world of youth sex trafficking is that in Washington, as in most other states, underage prostitutes are still legally considered criminals while simultaneously being regarded as victims.

In 2009 and 2010, 153 youths in eight Washington state counties surveyed were arrested and referred to detention on charges of prostitution, the youngest 12 years old, according to Shared Hope International, a faith-informed nonprofit dedicated to rescuing women and children in crisis and founded by former Washington state Congresswoman Linda Smith.

Victim advocates point out that this is incongruent with state laws — including the law that sets age of consent at 16, making it illegal for a 15-year-old to consent to sex, but legal for her to be charged with prostitution; and the fact that a minor younger than 18 cannot legally enter a contract. It is also inconsistent with United Nations protocols on human trafficking and the federal Trafficking Victims Protection Act, which defines any commercial sex act performed by a person younger than 18 as human trafficking, regardless of force, fraud or coercion.

Advocates say that arresting and charging minors for prostitution-related crimes also means that, despite some of the most progressive actions in the nation, Washington isn’t truly a “safe harbor” state. (Safe harbor laws define sexually exploited children as victims, provide systemic protection and services, and grant immunity from prosecution for prostitution.) They want the state criminal code on prostitution amended to encompass only adults older than 18.

“These are victims, not criminals,” says Terri Kimball, coordinator for Project Respect, a statewide project to create a victim-centered response protocol for agencies that come into contact with trafficked minors.

“We need to decriminalize this for minors,” echoes Giovengo. “The way this will change on a large scale is when we recognize them as victims of domestic violence.”

But police and prosecutors say the threat of criminal charges is often the only way to detain youths and get uncooperative kids to provide evidence against pimps and buyers.

“We need them to talk to us,” says SPD Detective Bill Guyer, whose youngest victim was 12. “Without [the ability to detain them], we have to just drive them to a bus stop.”

Advocates of decriminalization disagree, saying there are many legal justifications and frameworks to hold a juvenile, provide services and allow prosecutors to build cases against pimps and buyers.

It’s a fundamental question that goes unresolved — how can these children be victims and criminals? — even as cooperative efforts to rescue kids from trafficking and punish those who fuel the system hurtle forward.

Outreach efforts

The year 2012 was big for anti-trafficking efforts in Washington state: 12 bills were passed by the Legislature. The most controversial, SB 6251, made it illegal to knowingly publish an escort ad online or in print that involves a minor. But a lawsuit was subsequently filed by Backpage.com, and the law was blocked. The other 11 laws stand; legislators are now trying to address the problem of escort ads from another angle, by increasing punishment for those placing such ads.

Eventually there will be a push to exempt minors from prosecution for prostitution crimes, says Sen. Jeanne Kohl-Welles, D-Seattle, a longtime champion of trafficking-related bills.

“We’re building support,” she says.

Project Respect, a $200,000, two-year pilot program that is spreading a new statewide protocol for response to young sex trafficking victims, also launches this year. “Our goal is to make sure everyone has the same training,” says Kimball, the project’s coordinator. “It’s not piecemeal.”

A plan to create a statewide database to identify young victims is also afoot, but not fully funded.

Detective Taylor, who, along with two police partners, opened The Genesis Project, a drop-in center for sexually trafficked minors and women in south King County, two years ago, says they are close to receiving enough funding, public and private, to stay open 24 hours a day.

Detective Taylor, who, along with two police partners, opened The Genesis Project, a drop-in center for sexually trafficked minors and women in south King County, two years ago, says they are close to receiving enough funding, public and private, to stay open 24 hours a day.

StolenYouth, a new nonprofit in Seattle, is hosting its first luncheon on April 17 and aims to raises hundreds of thousands of dollars to contribute to local wraparound efforts.

“People know this happens in Nepal, India, Cambodia, but to have it happening in Westlake Center, they cannot believe it,” says Patty Fleischmann, president of StolenYouth.

Ultimately, though, you can’t pull kids out of “the life” unless they want it.

“You might have the fluffiest linen in the world, the nicest shelter, but if you don’t offer them what they need — a way to be self-sufficient — and keep them busy and motivated, they will relapse,” says Briner, who notes that some research has found parallels between prostitution and addiction.

Broad outreach and services are the goal, and the glue is the small army of outreach advocates. The most effective advocates are sometimes survivors themselves.

“To really talk to these girls, you have to have been there,” says Gomez, who recently founded the Organization for Prostitution Survivors, counseling juveniles in the life and hosting a weekly survivor support group. She hopes to obtain funding for an all-ages service center.

‘Groomed’ for this

So, will cooperative agency efforts, caring survivors and donor money — the magic trifecta that seems to be brewing in Washington state right now — save kids from being sexually exploited commercially?

Not without a massive cultural shift, says Debra Boyer, an applied anthropologist, Humanities Washington speaker and author of “Who Pays the Price? Assessment of Youth Involvement in Prostitution in Seattle,” the 2008 guiding document in Washington.

Boyer has an even scarier message for parents than that given by police officers who warn that any girl, even from a “good” home, can end up on the street.

“In some ways, all girls are groomed for this. We’re talking about the sexualization and objectification of young girls in our media and our culture,” she says.

To create lasting change, we all need to watch for signs of abuse in all kids, talk about it and report it early on, Boyer says.

We need to educate kids about the grooming process, and empower boys and men to treat girls and women with respect, she says.

“Sooner or later, people have to stand up to hooker jokes. Don’t accept a strip club half a block from Safeco Field. Fraternities need to stop hiring women to come in to their parties. ... Men [need to stop] going to lunch at Hooters.

“We have to get people to stop buying women.”

See our Publisher's Note about this story.

TALKING POINTS

1. Ask your daughter whether she has ever been approached by a strange boy or man. Initiate a conversation about what was said to her and how she responded. Did she feel uncomfortable? Flattered?

2. Role play ways that your child can respond to catcalls, flirting and sexual compliments. Discuss what is normal and safe, and which scenarios are dangerous. Create a plan for her to respond that makes her feel both empowered and safe.

3. Know what your kids are doing on social media and with their phones. Discuss the long-term consequences that digital conversations can have. Set ground rules for texting and social media that include no sexual conversations or images at all.

4. Ask your teens directly whether they know anyone who is being abused or exploited. Chances are high that they have a friend who has been sexually abused and your child knows about it. Talk about what can be done to help.

5. Create a safety plan for when your kids are with their friends and not under adult supervision. Make checking in a requirement.

6. Does your tween or teen have a factual understanding of sex? Have you talked to your daughter or son about gender-based control and violence? Start the conversation early; by 12 most kids have already heard the details from somewhere. For a global perspective, watch the film Half the Sky with your son or daughter. Discuss their reactions and talk about solutions. Another good conversation starter is the documentary Straightlaced.

7. Build honest relationships with your kids. Don't judge. If your teen or tween is acting out, try to understand why. Ask them what they are going through. If they won't open up to you, seek out another adult whom they will talk openly to.

—Natalie Singer-Velush

TAKE ACTION

National Human Trafficking Resource Center

24-hour hotline: 888-3737-888

Washington Anti-trafficking Response Network

Victim Assistance Line: 206-245-0782

Polaris Project

State maps, tools and resources

Change.org Safe Harbor petition

StolenYouth

Donor and program funding opportunities

Seattle Against Slavery

Information on local efforts and a guideline on how advocacy efforts and legislation work and how to become involved

The Genesis Project

Accepts donations, clothing and supplies for victims and offers volunteer opportunities

The Organization for Prostitution Survivors

Learn and donate

20 ways you can help, from the U.S. Department of State

WATCH: "In Our Own Backyard," a Seattle Town Hall summit