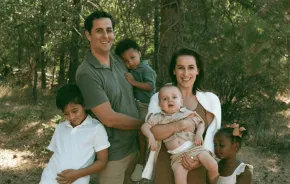

Not long after Rachel Trindle’s twin son Daniel was born with cerebral palsy, she noticed the friendships she’d cultivated with other parents just “withered up and died away.”

Not long after Rachel Trindle’s twin son Daniel was born with cerebral palsy, she noticed the friendships she’d cultivated with other parents just “withered up and died away.”

After all, her life as a mom had changed dramatically. No longer could she connect with parents of typical children as she did when raising her two older sons. Even more disconcerting, those same parents — the ones she’d spent so much time with — clearly didn’t comprehend the challenges she was now facing. “I’m dealing with major surgeries and the acquisition of a wheelchair,” says Trindle, a Bellevue resident. “I’m trying to listen to them talk about Disney vacations and I just cannot relate on any level.”

Trindle’s sense of disconnection is not uncommon for parents who have been suddenly thrown into a world of grief, medical jargon and awkward exchanges with family, friends and strangers, say Gina Gallagher and Patricia Konjoian, authors of the book Shut Up About Your Perfect Kid: A Survival Guide for Ordinary Parents of Special Children.

“Because we’ve struggled so much trying to find a place for our kids in this perfection-obsessed society, we become frustrated when other parents don’t share the same struggles,” they write. “And often [we] resent the fact that they don’t understand ours.”

Parents of children with special needs find it’s easier to spend time with other parents who have had similar experiences, a bond the writers wryly call the “imperfect connection.” Schools especially can be hotbeds for tension between parents. Yet, says Trindle, as the dust has settled in her life as the parent of a child with special needs — Daniel is now in fifth grade — she’s started to see the common ground that all parents share. “I deal with pretty much all the same things that a typical mom does,” she says, “and then there are some things that are unusual.”

Dealing with grief, loss

The term “special needs” refers to a range of developmental disabilities that can impact a person’s ability to move, communicate, learn, care for himself and live independently. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, these include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, cerebral palsy, autism, seizures, stuttering or stammering, hearing loss, blindness, learning disorders and other developmental delays. A study published last May in the journal Pediatrics found that 15 percent of children ages 3 to 17 years, or nearly 10 million children between 2006 and 2008, had a developmental disability, and that boys were twice as likely as girls to be affected. Many parents experience a profound sense of grief and loss when they realize their child is different

from typically developing children. Seattle mom Brenda Biernat is a photographer. Her 9-month-old son, Jasper, had a stroke at birth that caused mild damage to the visual portion of his brain. “I’m a really visual person and I literally had fantasized about visual things like showing him mountains or animals,” she says. “You grieve the loss of the dream you had and what you imagined it would be like.”

Her pain was especially potent when she was around other babies. At a mommy/baby meet-up shortly after Jasper’s birth, Biernat watched the babies sitting on the floor, all looking around. “It was just so hard to see that,” she says. “I ended up leaving early.” On the way home, she pulled over to the side of the road and cried. “I went through the whole ‘Why did it have to happen to him?’” she says.

The process of accepting a child’s disability can take years, says Susan Atkins, the Washington state coordinator for Parent to Parent, an organization that connects parents of kids with special needs to each other as well as to resources and information.

Atkins’ daughter Alexa, now 28, was born with Down syndrome. “It took me a while to be comfortable with Alexa having Down syndrome and not being typical,” she says. “I didn’t tell everybody for the first three or four years of her life that she had it.”

When Alexa was born, Atkins left the hospital with little information or support. A month later, a mother of a 3-year-old boy with Down syndrome called and offered to drive her to a support group for parents.

“She helped me so much,” says Atkins. “Parents with special-needs children are often the best resource for each other to get information and support.”

Biernat found a support group through Boyer Children’s Clinic, a Seattle-based facility that offers therapy and early childhood education to children from birth to 3 years of age. “This group has been my salvation,” she says. “It’s a really different experience from the typical mom.” The moms in her group share the grind of endless doctor’s visits and medication regimens.

“Those are your daily routines, versus the moms who are just raising their kids and doing the standard things,” she says.

Trying to connect

Trying to connect

Parenting a child with special needs can feel isolating. Ours is a world where young children ask awkward questions and strangers might peer disapprovingly at unusual behavior. Before Daniel was born, says Trindle, connecting with other moms was easy. “You have a parallel life and a lot to talk about,” she says. When a special-needs child enters the picture, things change.

“Suddenly, you’re uncomfortable to be around.” Trindle feels especially alone in public settings, since her son’s disability is so apparent. Daniel uses a wheelchairand a feeding tube, and has a voice output computerto help him communicate. Because people don’t know how to respond to Trindle and her family, they often ignore them, she says. “That’s one of the most uncomfortable things: to know that you are extremely visible, but to be treated as if you are invisible.”

While being ignored is unpleasant, being judged can be intolerable. Disabilities such as autism, not always obvious to onlookers, can provoke responses ranging from curiosity to downright disapproval. When autistic children, stressed by their environment, become frustrated or anxious, other parents mistake the meltdowns for misbehavior, says Kelly Johnson, a clinical psychologist at the University of Washington Autism Center. Many conclude the child needs more discipline. “There’s a lot of blaming of the parenting,” Johnson says.

Toby Beth Jarman’s 7-year-old son, Zachary, was diagnosed last year with Asperger syndrome, a mild form of autism. In preschool, Zachary had a tricky time with transitions and taking turns. Sometimes he’d push other kids. “Parents who didn’t know me thought he was a bad boy,” she says. “There was talk that I should be spanking him. Everyone had an opinion.”

In many cases, kids with special needs share classrooms with typical children — upping the pressure for parents of the special-needs kids. Parents of typical kids are sometimes wary of having a student with special needs in their child’s classroom, says Stacy Gillett, education ombudsman for the Governor’s Office. They fret that critical time or resources will be diverted from their own child’s education. “They won’t say anything directly to the parent,” says Gillett. Instead, “They will go to the principal and ask, ‘Did you make the right decision having this child in our class?’ or ‘Are you spending too much energy on this child with disabilities?’”

Fears and prejudices

Underlying those concerns are even deeper fears and prejudices, Gillett says. These range from the irrational worry that a disability might be contagious to discomfort with not knowing how to interact with someone who looks and lives differently. “These are very visceral responses from parents that are aimed at protecting their own children,” she says.

That tension is not lost on parents of kids with special needs. Jarman likens being the parent of a special-needs student to the person with the crying baby on the airplane. “Maybe people are being polite to your face, but you know nobody’s really that happy to see you,” she says. “And you’re going to do everything you can, you’re going to exhaust yourself trying to keep your baby from crying, but the fact is that baby is probably going to cry at some point and it’s probably going to annoy people, and they’re going to resent your presence.”

Jarman finds that people are not always forgiving or understanding, even if they know about a child’s disability. “Last year, my son wanted to have a playdate with this kid with whom he’d gotten into some fights earlier in the year, so I invited him to a playdate,” Jarman says.

The father expressed reservations; she explained that her son’s Asperger syndrome means he doesn’t always get social dynamics right. “It was a really awkward conversation. I could tell he really wanted to be big enough to get past his discomfort and let this happen, but in the end he wasn’t comfortable with it, and then I wasn’t comfortable with it.”

Jarman would like to feel welcome and accepted by the parents in her child’s class, but is reluctant to reach out to them. “Just the few negative interactions we’ve had with other parents have made me gun-shy,” she says. “But when people are outgoing and indicate that they are accepting, that goes a long, long way.”

Rachel Trindle agrees. “The kind of response that I love is when people make eye contact, smile and say, ‘Hi,’” she says. She understands that people may be worried that they will offend her by saying the wrong thing. “It’s never irretrievable,” she says. Some times, after awkward conversations, people tell her, “I feel really bad about the way I came across,” says Trindle. “We can go on from there and have a really good exchange.”

Trindle has learned to have a thick skin. Years ago, a parent from her other twin’s preschool, emailing about kindergarten, wrote, “You definitely want to avoid this class because I heard it’s going to have a totally retarded kid in it.” Trindle was shocked and hurt. Eventually she realized that the comment reflected the parent’s fear about her child’s ability succeed in a classroom with limited resources. “I can recognize that that fear is not about rejecting my child,” she says. “It allowed me to continue to interact with her.”

Helping others understand

Helping others understand

How can parents achieve better understanding and communication with parents of children with special needs — and with the kids themselves? How can they help their own children do the same?

Susan Atkins’ solution was to get involved with her daughter’s school. Each year, she introduced Alexa’s classmates to an “All About Me” book Atkins created. The book included pictures of Alexa as a baby and activities Alexa liked to do. Atkins also talked to her daughter’s classmates about Alexa’s Down syndrome.

At the end of the talk, she’d ask if anyone would like to be in Alexa’s “Circle of Friends.” That meant the kidswould eat lunch with Alexa and a teacher once a week and share pizza once a month. “They had an opportunity to get to know Alexa on a different level than just being in the classroom,” Atkins says. “It was always amazing how many kids raised their hand.”

Atkins says the Circle of Friends led to birthday party and playdate invitations for Alexa. “I got to know some of their parents well and still know them,” she says.

Parents of typical kids can also reach out to make social connections. The UW’s Kelly Johnson suggests that parents offer to have a playdate at either child’s house. Parents should try to find out what the child with special needs is interested in and whether there are certain times of day that seem to work best, she says. Initially, try to plan an activity that both kids will enjoy, “something that is really a special treat so that the activity itself is really enjoyable to both — and they happen to be together,” says Johnson. And when parents are socializing with each other, Johnson advises parents of typical children avoid discussing the special-needs child’s diagnosis. Instead, talk about the things any parent might chat about, she says.

Trindle says she appreciates those typical kinds of interactions. “I admire the moms who are able to get past the obviousness of the wheelchair and just ask how Daniel’s year is going,” she says.

Julie George, an education consultant at the UW Autism Center, is hopeful that the next generation will be more comfortable with people who have disabilities. With education and information, kids are usually quick to accept each other’s differences, she notes. “Kids can be really understanding. They just want to know what to do and how they can help.”

When Daniel was in first grade, one of his classmates felt bad that Daniel couldn’t eat candy on Valentine’s Day (he uses a feeding tube). So the classmate and his mother came up with an idea.

They created a bandana for Daniel that had the signatures of each student in the class. Since Daniel wears a bandana, this gesture embodied the level of thoughtfulness that Trindle cherishes. “That one kid who thought about Daniel as an individual,” she says, “if he ran for president of the United States, I’d vote for him.”

Stacey Schultz is a nationally published freelance writer in Seattle. She writes about parenting, health, education and the environment. Her website is staceyschultz.com.

Cultivating acceptance and empathy

How can parents help their children be more accepting of their peers with special needs? According to a report from abilitypath.org, an online community for parents and educators of special-needs kids, children with disabilities are two to three times more likely to be victims of bullying than their nondisabled peers.

Teaching children empathy and compassion is key to helping them understand the needs and limitations of others. In her book The Autism Acceptance Book, Ellen Sabin encourages children to “take a walk in someone else’s shoes.”

“When you take the time to understand people and walk in their shoes, you will be showing your kindness, learning about others, and being a good friend,” she writes. Sabin also advises children to be curious and open about people’s differences. “When people look or act differently than you, the best thing to do is to try to understand and accept them,” she writes. “Learn more about them, be kind to them, and include them in the things that you and your friends do together.”

Signe Whitson, author of Friendship & Other Weapons: Group Activities to Help Young Girls Aged 5–11 to Cope with Bullying, says parents should model compassion. “Children may listen to your words, but more importantly, they learn from observing your actions,” she says. “When you have a chance to practice a random act of kindness, do so.”

The abilitypath.org report suggests that parents can model inclusion by inviting children with special needs and their families to join in neighborhood activities, such as book clubs, PTA meetings and block parties, as well as to have playdates and attend birthday parties.

For older children, compassion and acceptance can be strengthened through volunteering in a peer buddy program, where a typical student is paired up with a student with special needs to develop social skills and foster friendships. Research shows that when children with special needs are included as friends in their social environments, bullying can be reduced.

Julie George, an education consultant at the University of Washington Autism Center, says that this kind of volunteering is beneficial for typical kids. “When kids work with children who have disabilities, their natural ability to help others and to teach comes out,” she says.

“Everybody wants to feel like they’ve made a difference and done something helpful.”

Great Books for Kids on Special Needs

My Friend with Autism, by Beverly Bishop

Be Quiet, Marina!, by Kirsten DeBear

A Friend Like Simon, by Kate Gaynor

All About My Brother, by Sarah Peralta